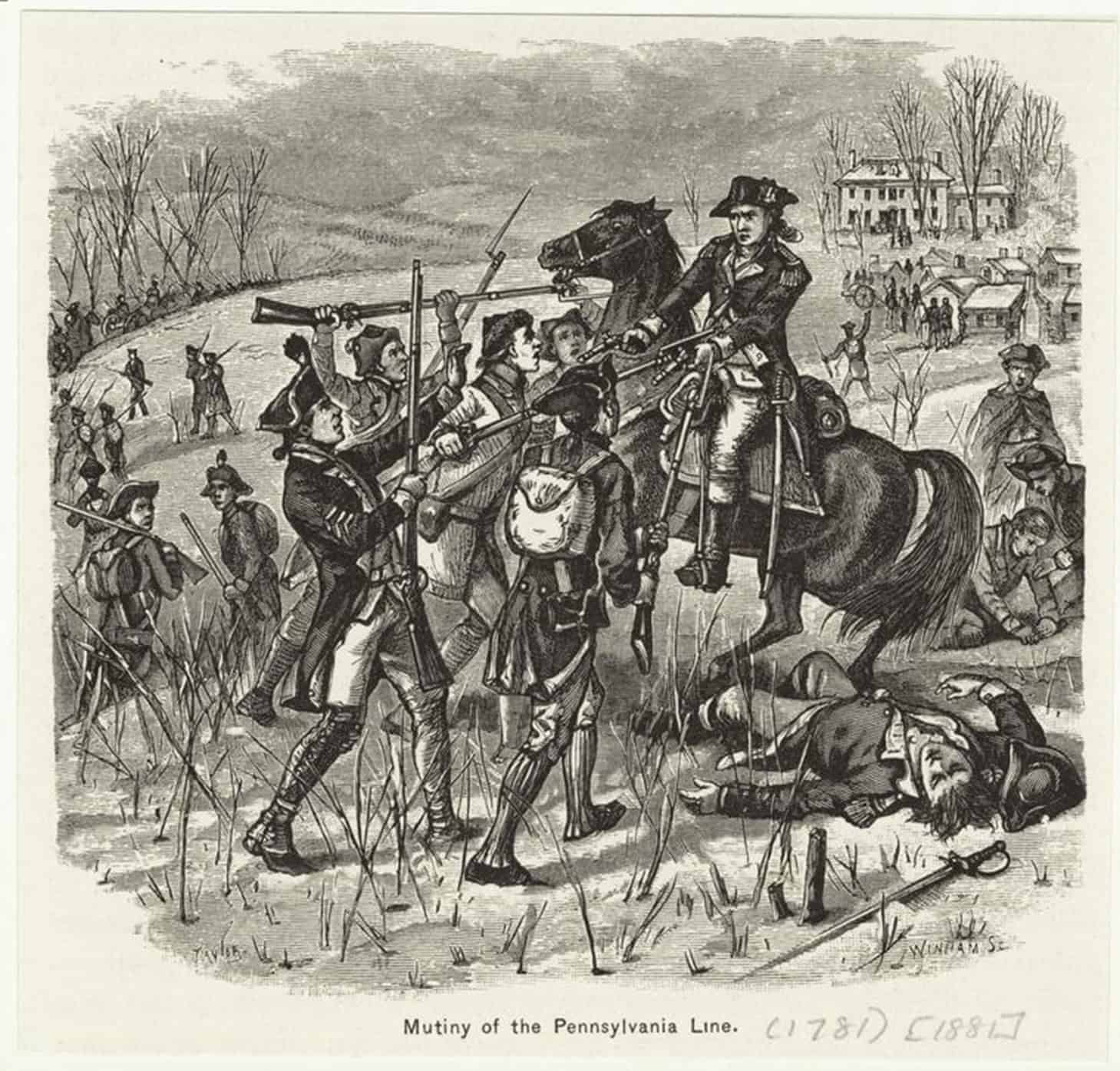

Not all casualties of war are inflicted by the enemy. This is a story of how our own Continental soldiers attacked and killed one of their own officers. It happened at the Mutiny at Morristown on New Year’s Day 1781, the most lengthy and successful insurrection by Continental soldiers throughout the entire war.

That winter would be the third of four total winter encampments in Morristown. The first two (1777 and 1779-1780) are most well-known because Washington set up his headquarters in town. But two following winters, 1780-1781 and 1781-1782, thousands of soldiers returned to Morristown without Washington and reused the huts they built at Jockey Hollow.

During this time, the collective grievances of years of suffering with insufficient supplies and lack of pay finally boiled over. By 1781 many soldiers of the Pennsylvania Line had served for three years or more, having received only a $20 bounty at enlistment, and even that had depreciated significantly because of runaway inflation. Meanwhile, new recruits were receiving a bounty of $200-$1000. Many of the men were enlisted for “three years or the duration of the war” and considered their enlistments over, though their officers insisted they needed to serve until the war was over.

With this underlying frustration as a backdrop, on the evening of 1 January 1781 the soldiers of the Pennsylvania Line drank heavily at a New Year’s party. Probably intoxicated, they took their rioting mob outside and paraded around Jockey Hollow, shooting their weapons. They even seized a cannon and began dragging it around with them.

Officers tried to calm them down and send them back to their huts. In the scuffle, Captain Adam Bitting, a German immigrant who commanded Company D, 4th Pennsylvania Regiment, was shot and killed by a mutineer. A lieutenant gave a description of Bitting’s death, “a soldier from the mob made a charge upon Lieut. Col. William Butler, who was obliged to retreat between the huts to save his life. He went around one hut and the soldier around another to head him, met Capt. Bettin who was coming down the alley, who seeing a man coming towards him on a charge, charged his Espontoon to oppose him, when the fellow fired his piece and shot the Captain through the body and he died two hours later.”

The mutineers decided to take their grievance directly to Congress in Philadelphia and insist on getting paid. By January 2, virtually the entire Pennsylvania Line, minus its officers, was marching toward Princeton with their cannon in tow. Their general, Anthony Wayne, followed behind, begging the mutineers to stop their folly and instead negotiate a settlement.

The mutineers arrived in Princeton on January 4, where they delivered a list of demands to General Wayne. They asked for immediate discharges for men enlisted in 1776-1777 at $20 bounty, and discharges after 3 years for those enlisted since 1777 at $120 bounty. They also asked for pay, clothing, and that there be no punishment for the mutineers.

The Supreme Executive Council, the highest governing body in Pennsylvania, sent president Joseph Reed to negotiate a settlement. When he arrived on January 7, instead of being treated badly, the entire line of soldiers lined up for inspection. They even wanted to honor Reed’s arrival by firing their cannon out of respect, but decided against it for fear it would worry the locals.

Meanwhile, the British got word of the mutiny and were jubilant. British General Henry Clinton sent two emissaries from New York to meet the mutineers and offer them full pardon and pay owed them by the Continental Army in exchange for joining the Redcoats. The spies were captured by the soldiers on January 7 and turned over for eventual execution. The soldiers made it clear that they were not about to defect and would hang any soldier who tried. They remained devoted to the Patriot cause throughout the whole ordeal.

Negotiations progressed quickly. The soldiers dropped all their demands except for one, that the “twenty dollar men” enlisted in 1776-1777 be given their pay and clothing and be discharged. They insisted that officers had tricked and punished soldiers to extend enlistments, and President Reed agreed. For the large number of soldiers whose enlistment papers were missing, Reed allowed men to simply give an oath to their time served. The sergeants representing the soldiers agreed to the plan, and on January 9 marched the soldiers to Trenton where they were met with supplies and clothing. Discharge proceedings started on January 12. Officers joined their units at Trenton, updated the rosters, and marched the remaining men back to Morristown. The Pennsylvania Line was reduced by more than half, from 2400 at the beginning of January to only 1150 men. The remaining soldiers formed into the Pennsylvania Battalion, which went on to participate in the southern campaign.

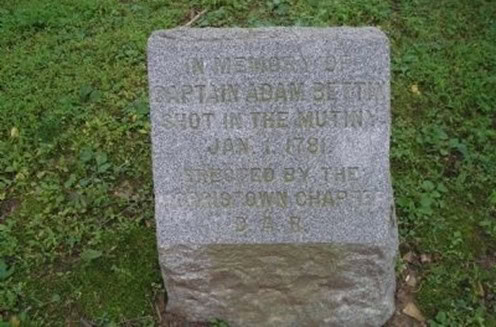

Morristown Chapter DAR placed a monument to Captain Bitting at Jockey Hollow around the year 1900, replacing an earlier monument. Local tradition claims that the monument marks Bitting’s burial site, but no documentation proves this. The monument reads:

In Memory of

Captain Adam Bettin

Shot in the Mutiny

January 1 1781

Erected by the

Morristown Chapter

DAR

Local tradition also claims that Bitting was buried near a black oak tree that was known as the “Bettin Oak.” A 1938 study found that the tree was more than 200 years old and would have been a well-developed tree of at least 10 inches diameter at the time of the mutiny, so this is possible, though unproven. The tree fell during a snowstorm in 1971, and a red oak sapling (the state tree of New Jersey) was planted in its place.

Mutiny of the the Pennsylvania Line, woodcut by Edmund A. Winhum & James E Taylor

Held at the New York Public Library

Photo from the Historical Marker Database at https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=8860

Sources

Morristown National Historical Park, Bettin Oak Monument, online at https://www.nps.gov/places/bettin-oak.htm

Yordy, Charles S. III, The Pennsylvania Line Mutiny, Its Origins and Patriotism, Penn State University Libraries, online at https://libraries.psu.edu/about/collections/unearthing-past-student-research-pennsylvania-history/pennsylvania-line-mutiny-0

_____, Mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line on history.com, online at http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/mutiny-of-the-pennsylvania-line

_____, Pennsylvania Line Mutiny on wikipedia.com, online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pennsylvania_Line_Mutiny