A SOLDIERS’ STORY: THE LEGEND OF SAMUEL MCILRATH

Samuel McIlrath (DAR ancestor A077200) has a mixed reputation. He was a respected church elder and a soldier in the Revolutionary War. But his reputation is tarnished by a local legend that he gave information to the British about General Charles Lee’s whereabouts that led to Lee’s capture at the Widow White’s Tavern in Basking Ridge on 13 Dec 1776. Did McIlrath do it? After reviewing the information, you can decide for yourself.

The Facts:

Samuel McIlrath was born in Aberdeen, Scotland on 25 Dec 1718. On 16 Mar 1755 he married Isabella Aikman, whose father also immigrated from Scotland. The McIlraths lived in Mendham, where Samuel was a respected citizen and Elder at the First Presbyterian Church. Even though he was somewhat older, during the Revolution he was a soldier in the Morris County Militia. His oldest son, Andrew, also served as a Private in the Militia and the New Jersey State Troops. Samuel McIlrath’s house in the Combs Hollow Historic District is still standing at 21 Combs Hollow Road in Randolph.

The Legend:

Local legend is that McIlrath encountered a British scouting party led by Lieutenant Colonel William Harcourt and informed them of General Lee’s whereabouts at the Widow White’s Tavern in Basking Ridge. Harcourt’s troops used McIlrath’s information to find the tavern, raid it, and take General Lee prisoner, supposedly while still in his nightclothes. What actually happened between McIlrath and the British is shrouded in mystery. The description of McIlrath’s encounter with the British varies widely depending on the source, and the story evolved over time.

Eyewitness Reports:

Contemporaneous reports from actual witnesses of the events mention that Harcourt’s scouting party obtained information about Lee’s whereabouts from informants. But no eyewitness mentioned McIlrath by name.

British Cornet Banastre Tarleton, who was part of Harcourt’s scouting party, described that Harcourt’s party “found by some people that General Lee was not above four or five miles distant, and at the same time heard that our retreat was cut off by the road we had come.” The informers were likely Loyalists who had heard that Lee was staying at Widow White’s Tavern. One of them may have been James Compton, a Basking Ridge resident who was later accused of, and admitted, assisting Harcourt’s party. [McBurney, p. 42]. One of them might have been Samuel McIlrath. Tarleton further explained a second encounter. “In going to the ground, I observed a Yankee light horseman, at whom I rushed and made prisoner…The fear of the saber extorted great intelligence.” [McBurney, pp. 43-44]. McIlraith could have been one of the civilians who either first informed Harcourt’s party that Lee was nearby at Basking Ridge, or provided directions to the village.” [McBurney, p. 235, note #70]. Tarleton also reported, “…my advance guard seized 2 sentrys without firing a gun. The dread of instant death obliged these fellows to inform me, to the best of my knowledge, of the situation of General Lee…These men were so confused that they gave us but an imperfect idea of where General Lee was.” [Olsen]

American General James Wilkinson was with Lee at the time of his capture, and wrote in his memoirs that “If a domestic traitor who passed his quarters the same morning on private business, had not casually fallen in with Col. Harcourt, on a reconnoitering party, the general’s quarters would not have been discovered.” [Barber and Howe, p. 445]

Secondary Reports:

An unknown member of Harcourt’s detachment informed British General William Howe’s aide-de-camp, Friedrich von Muenchhausen, of the raid. In a diary entry, Muenchhausen wrote that “early this morning he [Harcourt] chanced upon a light dragoon of the rebels who was on sentry duty. The sentry was about to shoot but was cut down before he could fire. Colonel Harcourt reasoned that, judging from the presence of the mounted guard, the enemy could not be far away. He thereupon pushed ahead and seized a second light dragoon on sentry duty before he could sound the alarm. Under emphatic threats of being hanged, the prisoner confessed that General Lee with a corps of 900 men was not far behind. Colonel Harcourt was about to force this fellow to lead him and his party to the house where General Lee was staying, but the sentry said that he did not know the exact location of the house.” [McBurney, p. 234]. Muenchhausen later recorded, “The [rebel dragoon] officer was captured in spite of his efforts to escape. Upon being questioned, the officer at first would not admit that General Lee was nearby. But when preparations were made to hang him, he not only confessed, but promised to lead Colonel Harcourt to General Lee’s house. Two dragoons, one on each side, rode with the officer, under orders given in his presence to cut him to pieces if he attempted to lead the Colonel and his dragoons to the wrong house, or into a trap.” [McBurney, p. 44]

Another British account was otherwise credible and consistent with von Muenchhausen’s. An officer of the 6th Regiment wrote that “in the morning he [Harcourt] fell in with one of their advanced sentinels, and dispatched a dragoon, who cut him down; he had not gone far when he perceived another, who he caused to be secured; while this was doing a horseman galloped up to the party before he perceived them. He was stopped and questioned by Col. Harcourt; he had a letter from [illegible] some rebel officers, yet denied knowing where Lee was quartered; but the Colonel ordered the rope to be got ready to tie him up; he, without further hesitation, pointed out the house.” [McBurney, p. 235, note #70]

Another British officer reported, “Col. Harcourt…observed a man on foot going with great expedition, whom he imagined to be a spy, and had him secured. On searching him, a letter was found, the wafer not dry, directed to General Washington from General Lee. The man was informed if he did not immediately conduct them to the house where the gentleman was who gave him the letter, immediate death would be his lot. He complied.” [Olsen]

Lieutenant Johann Heinrich von Bardeleben of the Hessian von Donop Regiment wrote in his diary that Harcourt had “captured an enemy captain, from whom he extracted various reports, among others that General Lee was staying at a house about seven miles farther away and had only a guard with him.” [McBurney, p. 235, note #70]

The Legend Develops Over Time:

Years later, British officer Charles Stedman, who served in the Revolutionary War and wrote a history of it, in part based on his interviews of fellow British officers, said of Harcourt: “Collecting information, as he advanced into the country, the colonel was induced to proceed farther. In his progress he intercepted a countryman [i.e., an American], charged with a letter from General Lee, by which he understood where he was, and how lightly he was guarded.” [McBurney, p. 235, note #70]

McIlrath is mentioned by name for the first time in 1846, by a Revolutionary War officer who knew McIlrath and believed that the British forced him to divulge information. “Col. J. W. Drake of Mendham, in conversation with one of the compilers of this volume, stated that the individual who acted as a guide to Col. Harcourt’s party was a Mr. Macklewraith, an elder of the Presbyterian church in Mendham. While walking in the road, he was suddenly surrounded by a party of British cavalry, who pressed him into their service.” [Barber and Howe, p. 445]. It should be noted that Col. Drake was a member of McIlrath’s church [Maurer], and therefore might have been more willing to give McIlrath the benefit of the doubt.

Over time, the story of McIlrath’s role took a more traitorous tone. In Munsell’s History of Morris County written in 1882, the story went like this: “The ‘Mr. Mackelwraith’ who has been accused of betraying General Lee to the British was Elder Samuel Mcilrath of Mendham. He was surprised and taken prisoner while walking along the road. He did not reside in the neighborhood and was ignorant of General Lee’s movements and whatever he did to point out any house where officers were quartered, or in any way to act as a guide to the British, he did under compulsion and to save his own life, and not as a traitor. Elder Mcilrath was as well-known as any man in Mendham, and it was known and read of all men that he was not a Tory.” [History of Morris County NJ, Munsell, p. 264]

In 1889, Andrew D. Melick was still willing to consider McIlrath honorably. “The capture of Lee was discovered later to have been in a measure accidental. It seems that Elder Muklewrath of the Mendham Presbyterian church, had been with the general the night before complaining that the troops had stolen one of his horses. On the following morning he fell in with a detachment of the 16th British light dragoons…which was reconnoitering the neighborhood. In some manner the elder divulged the proximity of Lee, and, it is said, either voluntarily or involuntarily, guided the enemy to the general’s quarters. Presbyterianism and patriotism were in such close alliance during the war that we are loth to believe that the elder willingly contributed to this catastrophe.” [Melick, pp. 344-345]

By 1921, McIlrath is not named, but implied in a biography of Charles Lee by Edward Robins. He wrote “…a Tory busybody had given the British…due notice of his presence in the tavern.” [Robins, p. 79]

By 1951, the informant was considered a Tory and British sympathizer, though McIlrath is not identified by name. “Four or five miles from Lee’s quarters Harcourt and his men met a British sympathizer, who told them they could not safely return by the route they had followed and informed them of the location of Lee’s army. Harcourt sent back a captain with four dragoons to reconnoiter, and then pushed ahead once more, taking the Tory with him. At a distance of a mile from Lee’s lodgings the British horsemen overpowered two American sentries and question them under threats of instant death. The sentinals informed them of the location of the army and also of Lee and asserted that Lee’s guard was a small one…Observing an American horseman approaching, they waited for him, forced him to surrender, and carried him off to their commander. He too was told he would be sabered unless he gave information, and he talked. He … admitted that he had just left Lee, and pointed out the tavern where the general had his quarters.” [Alden, p. 156]

You Decide:

Did McIlrath encounter Harcourt’s British scouting party at all, or were the informants other people entirely? Was McIlrath a willing traitor, or did Harcourt’s soldiers force the information from him? Was the informant a military man, a messenger carrying a letter to Washington, or a civilian? Had he met with Lee earlier, and if so, why would Lee still have been in his nightclothes? Was he on horseback, or on foot? Was he threated by saber, by a noose, or by nothing at all? Was he carrying a letter from Lee? Was his role confused with that of confessed informant James Compton? Only Samuel McIlrath knew the real truth.

Postscript – The McIlrath Family and Their Life After the Revolution:

Samuel and Isabella McIlrath had 3 sons and 6 daughters: Mary (b. 1756), Andrew (b. 1758), Agnes (b. 1761), Thomas (b. 1764), Jane (b. 1766), Alexander (b. 1769), Elizabeth (b. 1771), Isabella (b. 1774) and Sarah (b. 1777).

When the children were “middle aged, if not all of them married,” Samuel McIlrath and his family moved west, stopping first in Washington County, PA, then moving on to settle in East Cleveland, Ohio. It is said that “with other members of the family, they came in ox-teams, drawing household furniture, farming utensils, and the younger and frailer members of the party. They were six months making the journey, therefore they must have traveled at their leisure. They settled in a log house opposite Lake View Cemetery. Son Alexander and his brother-in-law, John Shaw, came on in 1803, and each purchased 640 acres of land, much of it fronting Euclid Avenue and extending north to the lake.” Son Thomas arrived in Ohio at about the same time.

Andrew McIlrath and twelve organizing members formed the Church of Christ in Euclid in 1807. This was one of the first churches in the Western Reserve (the land taken from the Native American and significantly offered as bounty land to Revolutionary War soldiers). Their earliest services were held in Andrew McIlrath’s home, and eventually moved to a log structure on land purchased from the McIlraths. The church later became known as The First Presbyterian Church of East Cleveland. Sarah McIlrath’s husband, John Shaw, became a ruling Elder of the church.

Abner McIlrath opened The McIlrath Tavern in 1837, located on the northwest corner of Euclid and Superior Avenues in East Cleveland. Some accounts state that his brother, Alexander, earlier ran a general store and tavern at the same location. The tavern distinguished itself as an informal community center. Abner owned a pack of foxhounds, and organized hunts and shooting matches at Thanksgiving and Christmas. A garden attached to the tavern was considered a local meeting place for women. For children, a small menagerie was maintained that included an eagle, a wolf, and a bear. Abner was celebrated for his size, purportedly 6’6 and 225 lbs. When Abraham Lincoln passed through Cleveland in 1861 on the way to his inauguration in Washington, he observed Abner standing in the crowd and laughingly invited him to measure up and see who was taller. They stood back-to-back and McIlrath won. “There,” said Abner, “you see I am a bigger Republican than you are!”

Daughter Sarah married and went with her husband to Pennsylvania, where she learned that her husband had murdered a peddler to get money to come and marry her. He was arrested, tried, convicted, and sentenced to hanging. She traveled alone on foot to the governor of Pennsylvania to solicit his pardon. Unsuccessful, she returned and remained with him to the last moment, and for three nights slept on his grave to prevent the doctors getting his body. Afterward she returned to Mendham, married John Shaw, and with the family moved to Washington County PA, then on to near Cleveland OH where they became wealthy. Sarah never had children, and her property was left to found the Shaw Academy, seven miles east of Cleveland.

Daughter Mary was disowned after becoming pregnant out of wedlock. When she was able to walk after the birth, McIlrath told her to pick up the baby and walk to the road in front of his house, where he told her never to darken his door again. She never did, and instead begged her way westward, finding a home among kind German farmers of western Pennsylvania “who had no more religion about them than to pity her misfortunes and by their kindness to heal her broken heart.” One of the farmers, James Hamler, married her and adopted her son, and their family moved to Ohio. Twenty years later, her sisters Sarah and Isabella learned of her whereabouts, immediately saddled their horses and rode through “almost unbroken wilderness a journey of nearly a hundred miles” to find her.

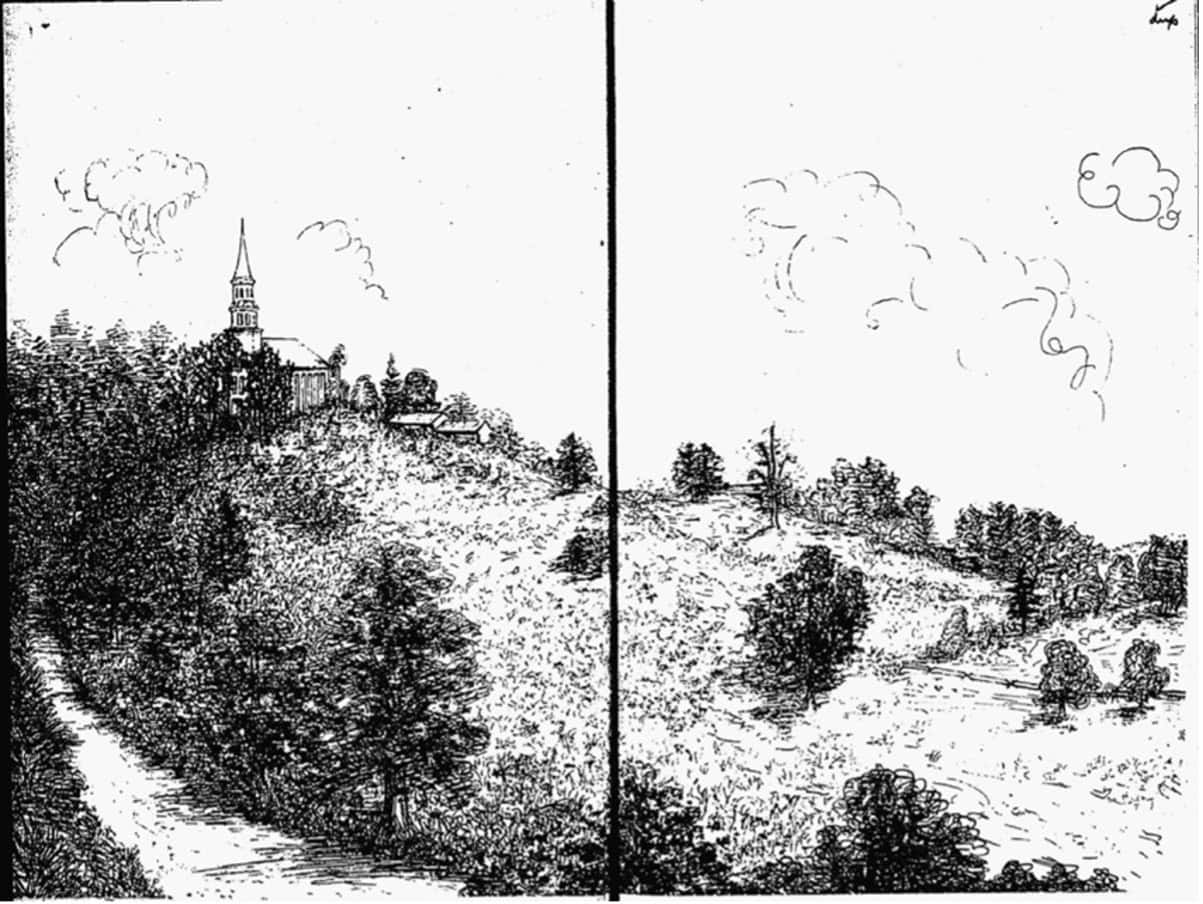

Samuel McIlrath came back to New Jersey on business, and while here he passed away on 9 Aug 1804 at the age of 85. He lived long enough to draft his will in Morris County, where it was filed on 23 Jan 1797. He is buried in the First Presbyterian Church’s Hilltop cemetery in Mendham. In yet another variation of the spelling of his name, his monument there reads “Samuel McHarth.”

Isabella McIlrath and their children are buried at the First Presbyterian Churchyard in Cleveland, Ohio.

From The First Presbyterian Congregation, Mendham, Morris County, New Jersey, History and Records by Helen M. Wright

The McIlrath-Lorey House, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:21_Combs_Hollow_Road,_Randolph,_NJ.jpg

Find-a-Grave memorial #9519783

Sources

Alden, John Richard, General Charles Lee: Traitor or Patriot?, Baton Rouge LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1951, pp. 154-161

Barber, John W., and Henry Howe, Historical Collection of the State of New Jersey, New York: S. Tuttle, 1846, pp. 444-445

Berg, Arthur R., Abstract of Early Wills (1801-1805), Archives of the State of New Jersey, First Series, Vol. XXXIX, Vol. X., Calendar of Wills

Daughters of the American Revolution, GRS (Genealogical Records System), Ancestor A077200 (Samuel McIlrath)

Find-a-Grave Memorial #9519783, online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9519783/samuel-mcilrath

McBurney, Christian M., Kidnapping the Enemy: The Special Operations to Capture Generals Charles Lee and Richard Prescott, Yardley PA: Westholme Publishing, 2013, p. 235

Maurer, C. F. William, Dragoon Diary: The History of the Third Continental Light Dragoons, Authorhouse, 2004, p. 447

Maurer, C. F. William, How Our Elder Changed American History, online at https://www.academia.edu/38426928/How_Our_Elder_Changed_American_History

Melick, Andrew D., The Story of an Old Farm: Or Life in New Jersey in the Eighteenth Century, Bedminster NJ: Unionist-Gazette, 1889, pp. 344-345

Olsen, Eric, notes on Charles Lee, unpublished manuscript held at the Morristown National Historical Park.

Patterson, Samuel White, Knight Errant of Liberty: The Triumph and Tragedy of General Charles Lee, New York: Lantern Press, 1958, pp. 163-168

Robins, Edward, Charles Lee – Stormy Petrel of the Revolution, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 45, no. 1 (1921), pp. 66-97

Wickham, Gertrude Van Rensselaer, The Pioneer Families of Cleveland 1796-1840, Vol. 1, Cleveland, 1914, pp. 72-73

Wright, Helen Martha, The First Presbyterian Congregation, Mendham, Morris County, New Jersey, History and Records, 1738-1938, Jersey City NJ: Camp News, 1939

_____, The History of Morris County, New Jersey, New York: W. W. Munsell & Co., 1882, pp. 243, 245-246, 264

_____, McIlrath-Lorey House, online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:21_Combs_Hollow_Road,_Randolph,_NJ.jpg

_____, Basking Ridge in Revolutionary Days: Extracts from a Lady’s Recollections, Somerset County Historical Quarterly, Vol. 1 (1912), , pp. 34-39, Plainfield NJ: A. Van Doren Honeyman