A Soldiers’ Story: Colonel Benoni Hathaway

Benoni Hathaway (DAR ancestor A052992, born 6 November 1743 in Morristown) has been described as “bustling” because of his many roles in support of the cause for independence. In battle, he was known to rush among the enemy “like a cannonball.” In their pension testimonies many years later, soldiers remembered and highly respected Hathaway as their leader. The extensive Hathaway family of Morris County sent at least fourteen men to join the army, including Benoni and at least five of his brothers.

In May 1775, only weeks after the battles of Concord and Lexington, Hathaway participated in a meeting of town leaders at Arnold’s Tavern in Morristown to prepare for a meeting of delegates of the Provincial Congress at Trenton. Hathaway brought a small cannon with him that he had purchased in Newark, intended to be used for patriotic occasions. A large and unruly crowd emboldened with apple brandy formed on the Green, highly animated to tar and feather Tories, and luckily the cannon was not used.

When the militia was formed in 1775, Hathaway was recommended initially as First Lieutenant by a meeting of the Morris County delegates held at the Dickerson Tavern on 14 September 1775. Soon after, he served as a Captain under Colonel Jacob Ford Jr.

At a battle at Elizabethtown on 8 December 1776, he was shot in the back of the head by a musket ball. He was carried off the field and remained under the surgeon’s care for several months while he recovered.

By late 1777, Hathaway was back in action, serving under Colonel Sylvanus Seeley, who replaced the deceased Colonel Ford. By August 1777, Hathaway was promoted to Major, and he was promoted again to Lieutenant Colonel on 13 November 1777. Around that time, he commanded a regiment of militia in skirmishes at Gloucester with British units led by Cornwallis, serving together with the Marquis de Lafayette.

He was appointed Colonel on 9 October 1779 and served in that capacity until at least 1780. During the “Hard Winter of 1779–1780,” a raging blizzard hit in early January, bringing transportation to a standstill. Officers who were not yet in huts had their tents blown down over their heads and then covered with several feet of snow. In the depths of despair, Nathanael Greene contacted anyone who could help. He wrote to Hathaway that the army was “on the eve of disbanding” and asked him to call out the militia and get as many teams as possible to break a path through the snow to a supply of provisions at Hackettstown.

During the battle of Springfield on 23 June 1780, Colonel Hathaway became angry at the leadership of his commander, General Heard. Afterwards he pressed charges by writing to Governor Livingston in a letter that demonstrates his tendency to action as well as his rough phonetic spelling:

Morristown, 17 July 1780.

To his Exelency the Governor. I send you in Closed Severel charges which I charg B D Haird with while he commanded the Militare Sum Time in jun Last at Elizabeth Town farms which I pray His Exilency would Call a Court of inquiry on these Charges if his Exilency thinks it worth notising from your Hum Ser Benonoi Hathaway Lut Coll.

This is the Charges that I bring against General Haird While he Commanded the Milita at Elizabethtown farms sum Time in June last 1780.

1 – Charg is for leaving his post and Marching the Trups of their post without order and Leaving that Pass without aney gard between the Enemy and our armey without giving aney notis that pass was open Between three and fore Ours.

2 – Charg is Retreating in Disorder Before the Enemy without ordering aney Rear gard or flanks out leading of the Retreat Him Self.

3 – Charg is for marching the Trups of from advantiges peace of ground wheare we mit Noyed them much and Lickley prevented thear gaining the Bridg at Fox Hall had not the Trups Bin ordered of which prevented our giving our armey aney assistance in a Time of great Destris.

4 – Charg is for marching the Trups of a Bout one mile from aney part of the Enemy and taken them upon an Hy mountain and kept them thear till the Enemy had gained Springfeald Bridge.

List of Evidence: Coll Van Cortland, Wm Skank the Brigad Major, Capt Benjman Cartur, Capt Nathaniel Horton, Adjt Kiten King, Major Samuel Hays, Leutnant Backover.

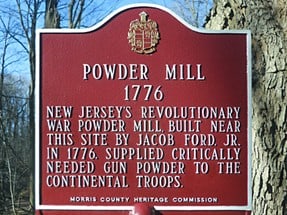

Some historians have reported that Colonel Hathaway also oversaw gunpowder making at the Ford Powder Mill along the Whippany River in Morristown. Though he did not mention this role in his pension application, commissary receipts confirm that he was involved in gunpowder production. The only gunpowder mill in all of New Jersey, this mill is said to have produced a ton of first-class gunpowder per month, providing much of the gunpowder used in the many battles and skirmishes in New Jersey. The powder mill was hidden away so completely among the trees and thicket that the eyes of no redcoat ever saw it. The mill itself is long gone, but there is a historical marker on its original site, reachable by walking on Patriot’s Path behind Acorn Hall.

Ford Powder Mill, from History of the “Arnold Tavern, Morristown N.J.

From revolutionarywarnewjersey.com

Hathaway also managed the powder magazine near the Continental Storehouse on the south side of the Morristown Green, where the finished powder was stored. He was always careful to exaggerate the quantity of powder being produced to mislead Tory and British spies. When the powder mill’s output was low, he would make “Quaker powder kegs” filled with sand instead of powder and deliver them with special demonstrations of sufficiency to fool any onlookers. At the powder magazine, he also managed the assembly of cartridges using the gunpowder.

Continental Storehouse, from In Lights and Shadows by Cam Cavanaugh

Living not too far from the powder mill, Hathaway kept a small cannon on his property to protect the approach to the mill, perhaps the same cannon he took to the meeting back in 1775. Many years later, depressions in the ground marked the supposed site of the cannon, and several cannonballs and a gun carriage wheel were recovered on the property.

After the war, Hathaway was a tanner and one of the largest early landowners, owning much of the land in the “Hollow” portion of Morristown. His house and farm sat on the road leading from Morristown to Speedwell, near where the Morristown Neighborhood House now stands. He became one of Morristown’s early developers, building Flagler Street across his property and selling lots as far east as Speedwell Avenue. He served on the committee that organized Morristown’s first Fire Association in 1797.

Home of Colonel Benoni Hathaway, from In Lights and Shadows by Cam Cavanaugh

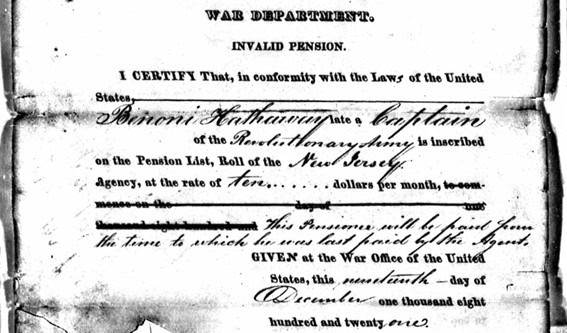

Benoni Hathaway received an invalid pension because of his war wound, but he was dropped from the roll in 1821 because he could not provide adequate documentation, paperwork which he never received. Lewis Condict appealed to the pension office, and eventually Hathaway’s pension was restored at the rate of ten dollars per month.

From the Revolutionary War pension file of Benoni Hathaway

Always superstitious, Hathaway was known to keep a horseshoe nailed above the door at his house to keep away evil spirits. After the war, his superstitions got the better of him, and he was famously duped by the swindler Ransford Rogers in what became known as the “Morristown Ghost Hoax.” Rogers convinced Hathaway that Tory gold was buried at Schooley’s Mountain, guarded by ghosts. He persuaded Hathaway and others to finance a search for the treasure, then pocketed the money.

Colonel Benoni Hathaway died on 18 April 1823 in Morristown. He is buried at the burying yard of the Presbyterian Church in Morristown.

Benoni Hathaway’s signature, from his Revolutionary War pension file

Sources

- Bartenstein, Fred and Isabel, A Report on New Jersey’s Revolutionary War Powder Mill, Morristown NJ: Morris County Historical Society, 1975.

- Carroll, Peggy, “The Morristown Ghost (or: Beware of Ghosts Promising Gifts),” posted 27 October 2016 on morristowngreen.com.

- Cavanaugh, Cam, In Lights and Shadows: Morristown in Three Centuries, Morristown NJ: The Joint Free Public Library of Morristown and Morris Township, 1986.

- Daughters of the American Revolution, Genealogical Records System (GRS), Ancestor A052992, Benoni Hathaway.

- Greene, Major General Nathanael to George Washington, 26 November 1777, online at founders.archives.gov.

- Hoffman, Philip H., History of the “Arnold Tavern,” Morristown N.J., Morristown NJ: Chronicle Press, 1903.

- Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, NARA M804, file S538 “Benoni Hathaway,” Record Group 15.

- Sherman, Andrew M., Historic Morristown New Jersey, Morristown NJ: The Howard Publishing Company, 1905.

- Thayer, Theodore, Colonial and Revolutionary Morris County, Morristown: Compton Press Inc., 1975.

- Tuttle, Joseph F., Annals of Morris County, ca. 1869.

- Varnum, General James Mitchell to George Washington, 21 November 1777, online at founders.archives.gov.

- Washington, George to the Militia of Certain New Jersey Counties, 20 November 1777, online at founders.archives.gov.