The story of William Mead, as told in his pension testimony (S31860), is a swashbuckling story of a man with major wanderlust and an incredible survival instinct.

Mead was born in New Jersey in 1740. By the time the Revolution erupted, at 36 years old he was already a little bit on the old side for a private, but that didn’t slow him down. He enlisted in Captain Peter Dickerson’s company in Morristown. We don’t know the exact date, but he reported that he served at the Battle of Long Island in the summer of 1776, so we know it was quite early in the war.

Mead testified that while he was stationed at Paramus, he and some of his colleagues left the group so that some of them could attend a wedding. Mead called this a “detached group,” but the army called it “deserters,” and today we would call it AWOL (Absent WIth Out Leave). They didn’t appear to intend to separate from the army permanently, but rather just take an unapproved break to go to the wedding.

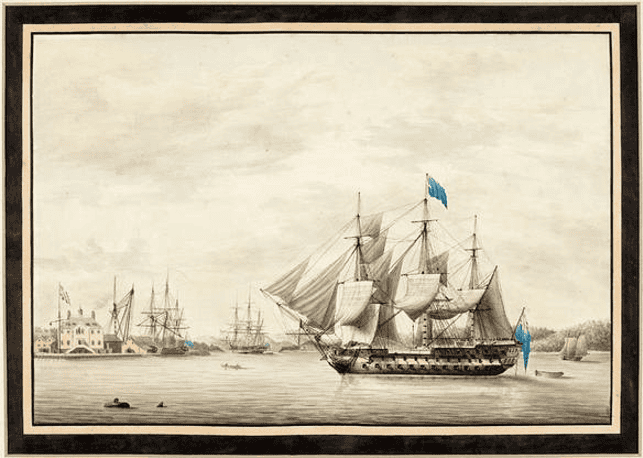

While they were “detached,” Mead’s group encountered a group of British soldiers and Tories, who took them prisoner. Mead ended up on board the prison ship Asia in New York. A picture of this ship is below, and here is a link for more details about it:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Asia_(1764)

The Asia sailed from New York to Charleston South Carolina with a group of prisoners, including our William Mead on board. He was imprisoned at Charleston, but somehow managed to escape with a couple of his buddies. He found the army of Generals Nathanael Green and Thomas Sumter “on the high hills of the Santee,” and decided to just rejoin the army there without properly enlisting.

But his adventures are not over. While with the army down south, Mead ended up in the Battle of Eutaw (pronounced “Utah” like the state) Springs, which took place on 8 Sept 1781. This was the last major engagement in the south, and one of the hardest fought actions of the Revolution. Americans suffered 139 killed, 375 wounded, and 8 missing. Mead himself was wounded, taking a musket ball in the shoulder and a bayonet wound in the thigh. But even though Green lost the battle, he won the campaign. Because of significant British losses (85 killed, 351 wounded, 257 missing), the British were forced to withdraw to Charleston, setting the stage for the victory at Yorktown only a few days later. If you’re interested in learning more about this battle, here’s a link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Eutaw_Springs

After Eutaw Springs (and presumably after he recovered from his wounds), Mead was dismissed from the army. But because he had never really properly enlisted with Green’s troops, he could not be formally discharged.

Mead participated in a very extensive list of battles throughout the war including Long Island, Fort Washington, White Plains, Brandywine, Woodbridge, Monmouth, Stony Point, Elizabethtown, Staten Island, Eutaw Springs, the Sullivan Expedition and its Battle of Newtown, and what he called the “expedition against the Mohawks at Johnstown” which is probably what many other soldiers called the Minisink expedition.

If that’s not exhausting enough, imagine how Mead spent the rest of his life wandering around the far frontiers of the south and west. He was in Edmonson County Kentucky when he applied for a pension in 1829. By 1830 he was in Madison County Illinois. In 1836 he was in Vanderburgh County Indiana, and in 1836 (at 96 years old) he was living with a son-in-law at Sangamon County Illinois. We don’t know exactly where or when he died.

Teddy Roosevelt espoused the value and honor of what he called the “strenuous life.” In a speech in Chicago on 10 April 1899 Roosevelt said:

“I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph.

Above all, let us shrink from no strife, moral or physical, within or without the nation, provided we are certain that the strife is justified, for it is only through strife, through hard and dangerous endeavor, that we shall ultimately win the goal of true national greatness.”

William Mead embodies the “strenuous life.” Roosevelt could’ve learned a thing or two from Mead.

HMS Asia in Halifax Harbor, by George Gustavus Lennock

From the Peter Winkworth Collection, Library and Archives of Canada

Sources

Pension of William Mead, S31860, National Archives and Records Administration, M804, RG 15

Credit: Susan (Bobbi) Bailey, State Historian, New Jersey Society Daughters of the American Revolution.