A SOLDIER’S STORY: SAMUEL SHELLEY

Morris County patriot and centenarian, Private Samuel Shelley (DAR ancestor A128276), was an interesting storyteller who provides valuable insights about military service during the Revolution.

Private Shelley chose not to apply for a pension until 1851, 68 years after the Treaty of Paris ended the Revolution, and when he was already 91 years old. In fact, he waited so long that he could not provide corroborating testimony from a fellow soldier (few survived by that point), and instead had to rely on testimony of children or even grandchildren of men with whom he served. Shelley’s pension testimony (R9470V) demonstrates his sharp mind and his incredible storytelling skills. I’ll tell his story here, borrowing liberally from Shelley’s own words.

Samuel Shelley was born in August 1760 at Hempstead Plains on Long Island. As the Revolution started, he was serving as an indentured servant in New York City. His father was a ship’s carpenter, who had escaped from forced labor with the British army. The family’s property was confiscated, and they took refuge in New Jersey at Canoe Brook (near Summit).

Shelley did not enlist into the army willingly. Even though he was about 19 years old in 1780, he used his youthful appearance to lie about his age and avoid the draft. Eventually, an elderly aunt inadvertently let the cat out of the bag. Shelley told the story this way:

“There were two American officers came to my father’s at Canoe Brook and desired a conveyance to Green Brook. My father sent me with them…I traveled in a sleigh across the fields and over the fences…When we arrived at Green Brook, I was asked concerning my age. I told them I was twelve. They let me pass, and I returned home. When I reached home, one James Ballard, an orderly sergeant in the army, came and inquired about my age. I told him the same thing. He then went to an old aunt of mine who was ignorant of his purpose, and from her he learned the truth. He then said to me, ‘My find fellow, I will take care of you. Do you not know that there is a heavy fine if you do not join the army when you get to your age?’ I told him I did not. Then he carried me off to Green Brook in a sleigh. When there, they tried to persuade me to enlist during the war. I did not like to do it. Then Colonel Dickinson and Captain Reeves told me I had better enlist for nine months and then they would give me clear, and I accordingly did so.”

Shelley might not have joined the army willingly, but once enlisted, he served bravely. He was on active duty during the battles of (second) Springfield and Connecticut Farms in June 1780. He remembered vivid details of the events which give us a unique window into how it felt to be a private in battle. Here’s how Shelley told the story:

“…we were marched to Baskingridge. Word came that the British, five thousand strong, with cannon and a troop of horse and large supplies, had crossed over from Staten Island to Elizabethtown Point. We were immediately set to motion to meet them, but before we had arrived at Connecticut Farms, they were burned to the ground. The British began their retreat. General Greene rode up and ordered the Jersey Brigade to take the Vauxhall Road and follow it on until we met a regiment which had marched by another road at a place where the roads came together. When we reached this point, we found the other regiment engaged with the enemy. The skirmish was short. The British retreated, and we followed on until we saw them cross at Elizabethtown Point. Captain Reeves was badly wounded at the point where the roads come near together. The ball entered his side and passed upwards, coming out near the breastbone. He recovered of his wound but died sometime afterwards from the effect of it. [Note: I tried to find this Captain Reeves, but was unable to identify him. Several other soldiers in addition to Shelley mentioned Captain Reeves’ death in their pension testimonies.]

“After the British crossed to Staten Island, we were marched around for some days until we reached Chatham. We there encamped. General Washington was there with us. His quarters were him a house below the academy. We were on the high ground beyond. We continued there until the twenty-second or -third of June, and then we heard the alarm guns fired, first one, then another, and again the third. We were all immediately aroused and busy. General Greene ordered the Jersey Brigade to Springfield. We marched to Springfield. Before we arrived, the Rhode Island troops had been engaged at the bridge near the meetinghouse and had been almost all cut off. Our colonel (Dickinson) rode up and ordered forty or fiftty of the spryest to go and cut off the British light horse. We ran across to a place where the road ran near a stone fence overgrown with sumac bushes. We concealed ourselves and fired upon the stragglers as they passed towards Day’s Mill. Many were killed. The British again retreated, and we again followed them to Elizabethtown Point. In the pursuit, they left their cattle near where Governor Livingston used to live. He, with his troop of horse, also pursued them and hurried them, so that they outran the Jersey Brigade. Just as they crossed on their boats, Washington descended the hill on one side and Greene, with his troops, on the other. Washington fired upon them with his cannon. It was his purpose to cut them off but was too late. Greene, fearing that some of the British might have gone up the creek to attack our rear, ordered a flank movement, and I was marched up the river. This was in the night. In the morning the British had disappeared.”

As part of his pension testimony, Shelley was asked an “Interrogatory,” which was supposed to be a set of ten standard questions asked of all soldiers (Where were you born? Where did you reside when you enlisted? etc.). I’ve read hundreds of pension testimonies, and every one follows the same formula, except Samuel Shelley’s. His Interrogatory was much more like an interrogation, continuing well past the basic questions and delving into details of his story: How long were you driving from Canoe Brook to Green Brook, and mention the incidents of your drive. How far is it from Baskingridge to Connecticut Farms, and how long were you marching there? Where did you go after returning from the pursuit? What occured when the guns fired? Perhaps the interrogator was trying to validate Shelley’s story, or perhaps he was enthralled by the graphic details that Shelley remembered and wanted to glean as much as he could from Shelley’s sharp memory. At one point in the Interrogatory, Shelley embellished his story some more:

“As we came near Springfield, we saw the church on fire. It appeared that before we came there had been a smart action by one of the bridges between the Rhode Islanders and the British horse. The Rhode Islanders fired away all their ammunition and fixed their bayonets, but the horse were too much for them and drove them back, crossed the bridge, and the foot followed…When twe came in sight, the streets of Springfield were full of redcoats. They had got past the meetinghouse and were firing the last house…When they got the last house burning, they then aimed for Day’s Hill, a village nearby. We were ordered to cut them off. Two or three hundred marched up, and a few stationed behind a stone wall, maybe fifty of us. The road ran near the river, and the scattered horsemen had to pass us. We dropped them as they came along. Some had two or three balls in them. We called all that passed except a little Irishman, and his horse was killed under him and he taken prisoner…

“When the pursuit began, we had one cannon with us. They rigged up an old horse to it and followed on after the British. He would ride up and pour it in on them…and they were mightily harried.”

Like so many others, Samuel Shelley was denied a pension, perhaps because he did not meet the minimum service requirements, or perhaps as one official noted. “at the time of his making his declaration, I was not aware that any corroborative evidence could be obtained…”

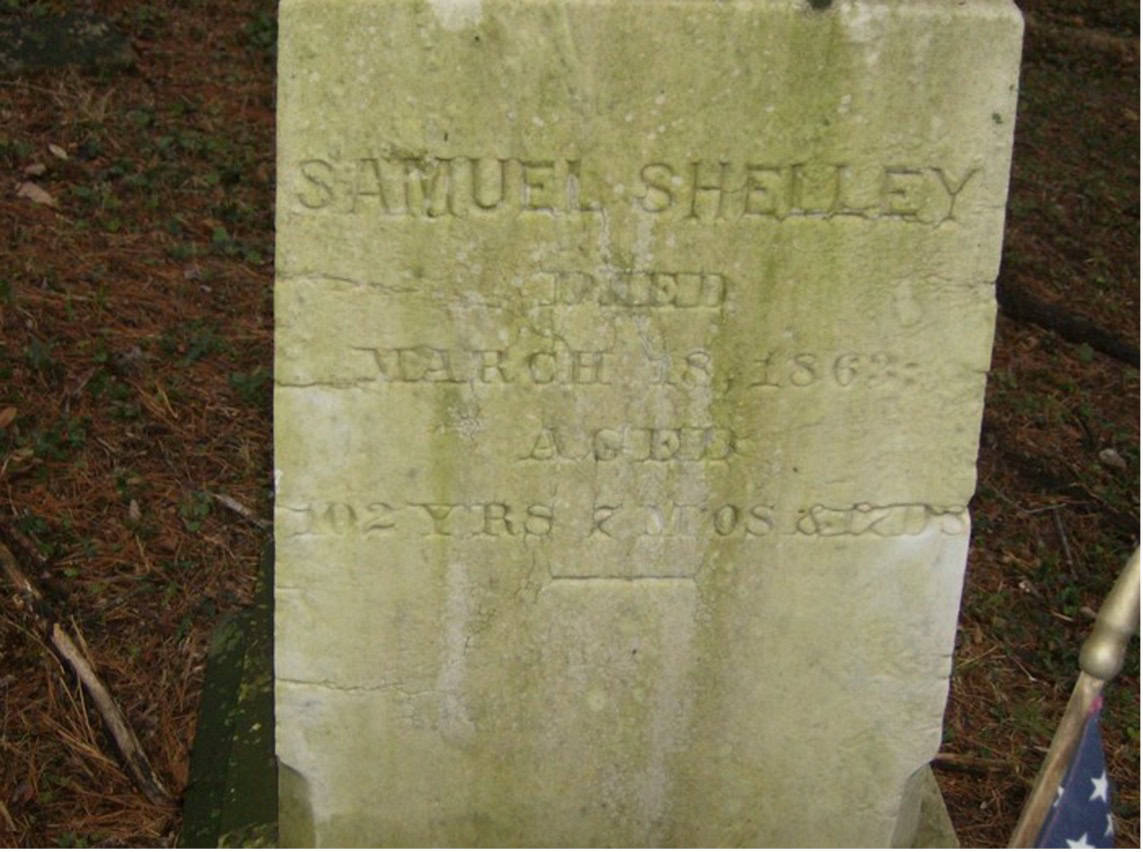

Private Shelley remained in New Jersey, marrying and raising his family in Sussex County. He lived to the ripe old age of 102, and was one of the last (if not the last) surviving Revolutionary War soldiers in the area. He died on 18 Mar 1863 in Sparta. He’s buried at the Deckertown Cemetery in Wantage, Sussex County.

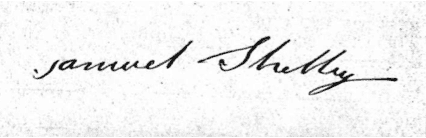

Samuel Shelley’s signature from his pension File, R9470

National Archives and Records Administration microfilm publication M804

Samuel Shelley gravestone, Find-a-Grave Memorial #6009684

Sources

Dann, John C.(ed.), The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for Independence, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1980, pp. 127-135

Daughters of the American Revolution, Genealogical Records System, Ancestor A128276 (Samuel Shelley), online at https://dar.org

Pension of Samuel Shelley, R9470V, National Archives and Records Administration, M804, RG15

Rees, John U., “I Extracted 4 balls by cutting in the opposite side from where they went in…” Miscellaneous Accounts of Continental Army Surgeons and Surgeon’s Mates, online at

https://www.academia.edu/34866852/_I_Extracted_4_balls_by_cutting_in_the_oposite_side_from_where_they_went_in_Miscellaneous_Accounts_of_Continental_Army_Surgeons_and_Surgeons_Mates