“they found a Leader in the brave Coll. Ford they followd him with Alacrity”

– Samuel Adams, January 9, 1777

Colonel Jacob Ford, Jr. & the Morris County Militia 1776

Morris County Militia to December 1776

In the early months of 1776, the British were besieged by Washington and the Continental Army in Boston. However, many feared that New York City would be the next British target, and the Patriot militias in the area began to prepare for war.

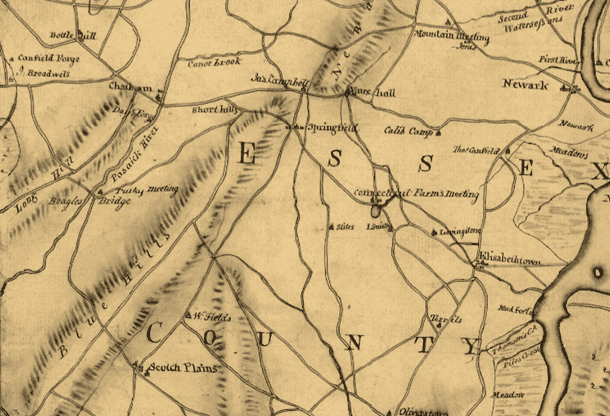

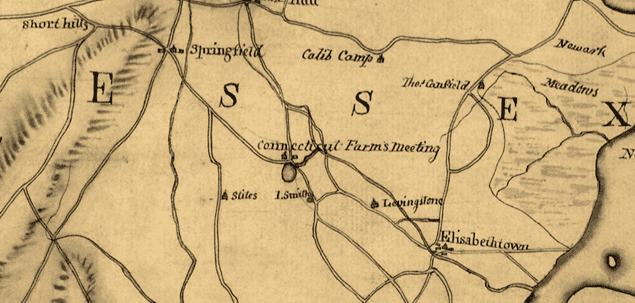

Morristown [far left] Springfield [center] and Elizabethtown [far right]

Job Loree was part of Colonel Jacob Ford’s militia regiment that performed duty in Essex County early in 1776. He remembered that he was “…in 1776 at Elizabeth town point before harvest & not long before the British took possession of New York. We lay in cloth tents, under command of Col. Ford… we were engaged in throwing up breast works for defense at the landings opposite Staten Island, not less than a month, when we were relieved and discharged… about the 1st June when I was first ordered to Elizabeth town. I performed a months duty at Amboy… Guarding the shore opposite Staten Island. Whilst there we heard much heavy firing which was afterwards understood were guns in the Long Island battles. We all staid a month & were relieved and discharged. In October following I performed a month’s duty at Elizabth. Town, stationed at the old barracks…”

Samuel Freeman was another member of Ford’s militia regiment. His first recollection of militia service was in August 1776, when Ford’s regiment “was marched from Morristown to Elizabeth town performing guard duty upon the lines & at the landing places guarding the inhabitants from plunder.” Isaac Bedell, a fifer, was also there. He recalled that he was “13 years old, was a Fifer in Captain Peter Layton’s company, in Colonel Jacob Ford’s regiment of Morris Co. Militia & in October and November 1776 performed in Layton’s Co. under Col. Ford at Elizabeth town when said Company were stationed performing guard duty & fortifying the landing places at the points against the incroachments of the enemy then occupying N. York & Staten Island.” Job Low remembered, “In the fall of 76, I was stationed at Elizabethtown under Colonel Ford in barracks, performing guard duty & building breast works opposite Staten Island.” Luke Miller stated in his pension application that he remembered Dr. Johnes care of the sick that summer at Elizabeth, “there were considerable numbers ill of Dysentry & fever, some at private homes & in barns & barracks.”

Another soldier of the Morris Militia at Elizabethtown was Israel Lee, who noted, “while he was at Elizabeth Town he heard the cannon which was fired in the battle [Battle of Long Island, August 27, 1776].” Israel Lee was serving in the militia as a substitute, as he explains here, “I was an indentured apprentice to John Mills living in Morristown, when the war began, having the trade of a Shoemaker, Tanner & Currier. The tannery required the time & personal attention of my Master Mills so much, that he could not be spared from it without much hazard: & at his request I performed several monthly tours of militia duty as his substitute, leaving him to take charge of the shop & tanyard.”

If you are familiar with Morristown, John Mills was the son of Timothy Mills and had taken over the operation of his father’s tanyard. The Timothy Mills house is the oldest surviving house in Morristown dated to 1740. The house at 27 Mills Street is near Burnham Park and Morristown High School.

Abraham Fairchild remembered attending a church service of the Patriot Presbyterian minister James Caldwell while on his militia tour, “When at Elizabeth town in the tour of 76 (the first one have spoken of) I attended a religious meeting in which Revd. James Caldwell [left], a warm Whig & Minister of the Gospel expressed his hostility against the British encroachment & I heard Doctor Johnes disapprove the warmth with which Mr. Caldwell expressed himself as being indiscret.”

Militia duty usually involved the tedium of guard duty at places like Springfield and Elizabeth. But on one occasion Samuel Freedman remembered an engagement with a ship that livened up their duty. “During this winter & whilst under Genl. Winds news was recd. Of a British frigate, lying at Amboy, receiving supplies of provisions &C., from Tory inhabitants & conveying them to the army then in New York. We were permitted as Volunteers to take the alarm gun, a long 18 pounder lying near Springfield to Amboy during the night. A fire was opened from this gun early next morning under the direction of Genl. Winds upon the frigate & after exchanging some shots the frigate cut her cable & moved off.”

Job Brookfield, of Morristown, also recalled his militia service in a pension application. Brookfield’s summary of his comings and goings in the Morris County militia gives a good example of the life of a militia soldier through the last six months of 1776, “His first tour of Militia service was performed as he believes in the months of June & July in the year 1776, the time of the landing of the British army was expected in New York, under the command of Col. Jacob Ford, in Capt. James Kuris Company & was himself acting as Ensign of said Company …was stationed at Bergen town, in sight of N. York city & quartered at the house of a Dutch man there, whose name is not recollected. Whilst at this place news of the Declaration of Independence was rec’d which greatly cheered us. Remained there one month, was dismissed with the company & returned home, where we remained only about two weeks, when an alarm being given, our company or half of them volunteered under Capt. Keen myself acting again as Ensign marched to Bergen again where we were stationed within sight of New York city.

Militia duty usually involved the tedium of guard duty at places like Springfield and Elizabeth. But on one occasion Samuel Freedman remembered an engagement with a ship that livened up their duty. “During this winter & whilst under Genl. Winds news was recd. Of a British frigate, lying at Amboy, receiving supplies of provisions &C., from Tory inhabitants & conveying them to the army then in New York. We were permitted as Volunteers to take the alarm gun, a long 18 pounder lying near Springfield to Amboy during the night. A fire was opened from this gun early next morning under the direction of Genl. Winds upon the frigate & after exchanging some shots the frigate cut her cable & moved off.”

Job Brookfield, of Morristown, also recalled his militia service in a pension application. Brookfield’s summary of his comings and goings in the Morris County militia gives a good example of the life of a militia soldier through the last six months of 1776, “His first tour of Militia service was performed as he believes in the months of June & July in the year 1776, the time of the landing of the British army was expected in New York, under the command of Col. Jacob Ford, in Capt. James Kuris Company & was himself acting as Ensign of said Company …was stationed at Bergen town, in sight of N. York city & quartered at the house of a Dutch man there, whose name is not recollected. Whilst at this place news of the Declaration of Independence was rec’d which greatly cheered us. Remained there one month, was dismissed with the company & returned home, where we remained only about two weeks, when an alarm being given, our company or half of them volunteered under Capt. Keen myself acting again as Ensign marched to Bergen again where we were stationed within sight of New York city.

We saw the British fleet sail into New York bay [above] & the army land a part in the City, & as they marched off from the wharves & a still greater part on Long Island. Remained there on this occasion he cannot tell how many days, but probably we were marched to Elizth town where we were stationed with our company & quartered at the Stable of one Baltus Dehart & slept upon some flax we found there. Whilst here, the battle of Long Island was fought in which our army was defeated, under Lord Stirling. We heard very distinctly the cannonading all day, as well as the musketry. Col. Jacob Ford was the commander of our Regiment. We remained one month out, were dismissed & went home. The next monthly tour was most probably in the fall, under Capt. Austin Baily, myself Ensign. Stationed again at Elizth town & quartered in tents – Duty was to guard the shores & landing points – building forts & breast works & protecting the inhabitants from being plundered by the tories & refugees & by the British, then possessing N. York & Staten Island. …our tents were pitched behind a breast work near Dharts point & the enemy on one occasion came close to the Staten Island shore with some field pieces or cannon fired into our encampment & overturned the tent of one of our neighbors & shattered a black walnut tree near us, but killed none. The next tour was performed at Elizth town & we quartered in log huts in rear of the breast work at Dharts point, under Capt Keen & myself Ensign. The Col. Not recollected. Sometimes Col. Bott & others Col. Thomas commanded whilst we were at Elizth town & sometimes Genl. Winds commanded the whole. Our duty was the same as before described. Stayed out our time & were dismissed. We returned home & remained but a few days before an alarm was given & we were ordered out or volunteered again, under Capt. Keen, myself Ensign. We marched from Morristown by Westfield & fell in with the rear of the main army under Genl. Washington then retreating thro’ the Jerseys. This was in cold weather & the march was called the “mud rounds” & performed probably in December, a little before the capture of the Hessians. Our company proceeded as far as New Brunswick with the main army & then parted, the army going toward Princeton & our corps of Militia filed off to Bound Brook. Pluckamin & thence to Morristown. We were marched almost immediately to Chatham upon another tour, under Capt. Keen again, being in cold weather – quartered at the home of Nathl. Bonnel, upon guard duty, thr British then lying in n. Brunswick & frequently sending out plundering parties….

The next tour of duty was performed at Springfield under Capt. Keen & Col. Jacob Ford. Stationed at the house of Walter Smith & upon guard duty as before stated. A party of the enemy about 500 came out by way of Westfield & we fell in with them at Springfield in the road, in front of the tavern where we had a smart skirmish in which Robert Pollard of the Sand Hill company was shot through the breast, but was not killed, altho’ his breath passed through the would, bubbling through it with the blood at each breath. He survived & recovered. Col. Spencer of Elizabeth town was with us on this occasion & had his horse shot under him. He dismounted & carried off his saddle with him. The British then retreated, stopped at Westfield & carried off with them the bell of Westfield Church probably to prevent its being rung in times of alarm.”

As a Colonel of the Morris County Militia, Jacob Ford experienced militia service at a much more complex level with additional challenges. One of his biggest challenges was maintaining the morale of his men who were by law forced to leave their family, homes, and farms to serve for periods of weeks, a month or an undetermined amount of time in cases of emergencies.

In April 1776 Col. Ford wrote to General Washington trying to get pay for a detachment of his men that had been sent to New York. On April 19th he wrote that he wanted Washington “to point out some Ways & Means” of speedily paying £289 to a detachment of 150 Morris County militiamen for eighteen days of Continental service at New York. The detachment marched to New York under Major Doughty in response to a request for aid made to the county committee of safety by Lord Stirling when he was Continental commander in the city. Although Stirling promised that the militia would receive “the same Provision & Pay with the Continental Troops in the Middle Department . . . much Jealousy subsisted in the Minds of the above Men upon marching, as to the Propriety of the Application from his Lordship to the County Committe, & thence many hastily concluded, that the Application being improper, the Pay & Subsistence might be uncertain.” To placate his men Ford promised to pay them out of his own pocket. He told Washington, “Your Memorialist, fearfull of any Delay, & anxtious to remove every Doubt in the Minds of his Men, became Surety & pledged his Faith, that the Men should be paid at some short Day after discharged from the Service or become Pay Master himself.”

Bergen Neck [center]

By the summer of 1776 the British were in New York harbor increasing the demands on the militia, especially Ford’s Morris Militia. General Washington wrote to General Mercer on July 4, 1776, “Upon full consideration of all circumstances I have concluded to send the Militia Home except 500 to guard Bergen neck, which I deem an Important post & capable of being used very much to our prejudice. I am also of Opinion that a body about Woodbridge & Amboy would be very usefull. I propose to retain the Morris County Militia for the first Purpose and leave It to Genl Livingston to order the Security of the other places—As to the Militia who have marched from distant Parts—I suppose like all Others, they are impatient to return to their Farms & Business & as others are dischargd It will be difficult to keep them. however that I leave to Genl Livingston who If he thinks they are necessary for the defence of the province will give them his orders—But I do not require their service any longer.”

Four days later on July 8th, General Hugh Mercer wrote to Washington and mentioned some of the work of the Morris militia on Bergen Neck. He also mentioned a potential morale problem. “On examining Bergen Neck I found some stock of black Cattle & Horses still remaind there—and that some familys on the Point held an Intercourse with the Enemy—Col. Ford assured me he would have all those removed to day—His force amounts to no more than 350, and those begin to be dissatisfyd at remaining on Duty while the Militia of the Neighborhood are dismissd—after leaving proper Guards at the Ferries of Hackensack and Pessac [Passaic]—there is not a number sufficient in this Quarter to reinforce the Party on Bergen Neck to 500—We are informed of a Body of Militia being on the March from Pennsyla—on their arrival I shall order part of them to Bergen Neck.”

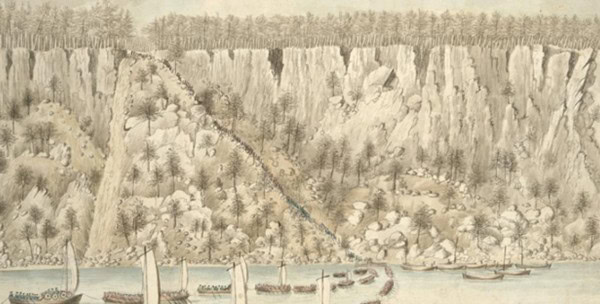

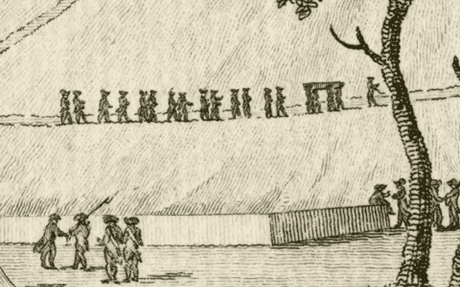

British Army ascending the NJ Palisades to attack Fort Lee

By September 1776, New York City was in the hands of the British. Fort Washington in northern Manhattan fell on November 16th. Then the British invaded New Jersey [above] capturing Fort Lee on November 19th. On November 26, Colonel Ford received the following orders from the head of the New Jersey militia General Williamson, “By express just now received from his Excellency Governour Livingston, I am desired to call out all the Militia of this State; therefore, on the receipt hereof, you are ordered to bring out all the Militia in your County immediately, and march them down to Elizabethtown, and see that each man is furnished with a gun, and all his ammunition, accoutrements, blanket, and four days’ provision, and when they arrive, to join their respective companies and regiments…P. S. SIR: You will please to send two men off to your County, express, with your orders to have these orders immediately put into execution. Order the express to call on me, to take a letter to Sussex.”

Governor William Livingston wrote to Washington the following day on November 27, 1776.

I have directed General Williamson to order all the militia of the Counties of Bergen Essex Morris Sommerset Middlesex & Sussex (having myself ordered that of Hunterdon) immediately to march & join the Army under your Command & to continue in Service for the defence of this State for a time not exceeding six weeks to be computed from the time of their joining the said Army.

The Legislature of this state has made Provision for raising four Battalions of 8 Companies each & 90 men to be inlisted till the first of April which will be carried into Execution with all possible Dispatch.”

The four battalions were also known as short term levies. They would relive the militia by serving longer than the militia soldier’s normal monthly term. By serving for four months, it was hoped that they could support Washington’s army long enough to allow new troops to be recruited for the Continental Army who would serve for a period of three years. As an enlistment inducement the State of New Jersey offered new recruits to the levies a bounty of 6 dollars plus one pair of shoes and one pair of stockings.

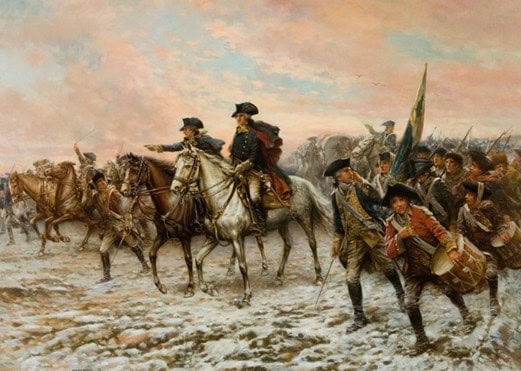

Mud Rounds Retreat

Things changed for the men of the Morris County Militia when the British invaded New Jersey at Fort Lee in November 1776. At the time, Colonel Ford and his contingent of the Morris County Militia were posted in Elizabethtown [modern Elizabeth]. Washington’s army began a slow retreat across the state, probably reaching Elizabethtown on November 28th. Ford’s regiment then joined Washington’s retreat. Samuel Freeman recalled, “Deponent with his company and other Militia forces followed on in the rear as far as New Brunswick where the Militia separated from the main army & marching by Bound brook thro Somerset went to Morris town.”

This was a new revelation for me. In my previous research on Colonel Ford’s military service, I had never run across any reference to Ford’s regiment joining in Washington retreat. But several other pension applications confirm Samuel’s statement. Isaac Bedell recalled, “Our regiment lay in the town [Elizabethtown] & at the landing points until General Washington with his army passed through Elizabeth town towards N. Brunswick, late in November or early in December, on what was called the Mud Rounds march. The Morris Regiment under Col. Ford fell in with the rear of the retreating army & followed it a few miles S. West of N. Brunswick where they were discharged & marched to Morris town by Pluckemin and Basking Ridge. Doctor Johnes was with the Regiment on the whole tour, which was not less than 14 weeks. When near Plainfield & before reaching Brunswick, a man became disabled from fatigue or some injury, & I recollect Doctor Johnes being directed by Col. Ford to attend to him.”

Job Loree noted that that the retreat was known as the “Mud Rounds” because “the mud being almost knee deep.” He added, “we did not get home till late in November, being on duty not less than 7 weeks.”

Route of Morris County Militia in Mud Rounds from Elizabethtown [upper right] to Brunswick [lower left]

As the rear-guard, Ford’s men were the closest to the pursuing British as they protected the retreat of Washington’s army. By the time they reached New Brunswick the Morris County militia’s time of service was up, which was their reason for leaving Washington’s forces. Most of the men probably wanted to leave so that they could go back to Morris County to protect their homes, property, and families. No matter the reason, they probably left Washington around December 1, 1776.

Once they returned to Morristown, they had little time to rest. General Matthias Williamson, one of the commanders of the New Jersey militia, wrote from Morristown to Washington on December 8, 1776, “I wrote Letters to the commandg Officers of the Militia of this State, to draw out their Batallions, & join the Army under your immediate Command, or the Corps under my care, as most contiguous. I am sorry to say, that altho there was great necessity for them to exert themselves at this important Crisis, very few of the Counties of Essex or Bergen join’d my Command….”

However, he also praised Colonel Ford and the Morris Militia, “Coll Fords Regiment makes up the principal Part of the Troops here, and it is chiefly owing to his zeal in the American Cause, as well as his great influence with the People, that the Appearance of Defence at this Post has been kept up.”

But General Williamson was sick and had turned over his command temporarily to Colonel Ford noting, “my Indisposition puts it out of my Power. Collo. Ford has had the Command, since we arrived here. I took so great a Cold on the late March, which fell into my Limbs, as has in a great Measure confined me to my Room, & disabled me from joining the Brigade.”

General Williamson concluded his letter to Washington stating, “Upon the whole I am so entirely disabled from doing my Duty in the Brigade, by my Lameness, that I have wrote to Governor Livingstone, to request his Acceptance of my Resignation, and have ventured to recommend Colo. Ford as the properest to succeed in that Command.” Williamson was proposing that Colonel Jacob Ford should become a Brigadier General in the New Jersey Militia.

While General Williamson wrote his letter, militia private Israel Lee recalled a minor action he was involved with on December 8, 1776. “The Militia had to keep a strong guard on active duty all winter to watch their movements & drive back their plundering parties. We were stationed on guard duty at Springfield & on the Elizabeth town road nearly all winter. Whilst on this cold weather tour Capt. Benoni Hathaway of Morris County conceived the project of attempting to take a strong picket guard of the enemy stationed near the mansion house of Governor Livingston [Liberty Hall in present-day Union] which he had evacuated & which was near Elizabeth town. I volunteered to be on the party with him. As we approached the sentry & came near him, our Captain being in front the sentry perceived Hathaway by the light of the fire (burning the fence behind which we were partly concealed) The Sentry & Capt. Hathaway both fired at the same instant as tho it even but one report . The sentry was killed & Hathaway dangerously wounded in the side of the neck & near the ear. We all rushed in with fixed bayonets, killed several & brought off 30 or more prisoners & our wounded Captain.”

The wounded Captain Benoni Hathaway recounted his wounding in a pension application stating that he received, “A wound in the back part of his head from a musket ball, which entirely disabled him & in consequence where of he was carried off the field & remained under the care of the surgeon of said Regiment for several months before he was able to attend to any business.”

The home of Governor Livingston, where Benoni Hathaway was wounded, is noted on the above map between Elizabethtown [right center] and Connecticut Farms [center].

On December 12, 1776, Elizabethtown minister, Reverend James Caldwell writing from “Turkey” [modern New Providence, left center above] updated General Charles Lee about British movements and the local militia. At the time Lee was marching from Morristown to Basking Ridge. Unbeknownst to either man, Lee would be captured the following morning by a British cavalry patrol.

Reverend Caldwell wrote that he had learned of “the enemy’ s motions. From sundry persons who have been upon the road between Brunswick and Princeton, I learn the Army has very generally marched forward; indeed, all except guards of the several posts. Yesterday they sent a reinforcement to Elizabethtown from Amboy, of near one thousand. Some say the whole at Elizabethtown are about one thousand; others say fifteen hundred…I believe Elizabethtown is their strongest post, as they were afraid of our Militia, who have taken off many of the most active Tories, made some prisoners, and among others, shot their English Foragemaster, so that he is mortally or very illy wounded.”

British outposts December 1776 – New Brunswick [“Brunswick City” in bottom left], Perth Amboy & Staten Island [bottom right]

He also mentioned the activities of Colonel Ford and his militia on December 11th, “A company of our Militia went last night to Woodbridge, [on map Woodbridge is above Perth Amboy] and brought off the drove of stock the enemy had collected there, consisting of about four hundred cattle and two hundred sheep. Most of those cattle are only fit for stock [breeding rather than for immediate eating]. Colonel Ford begs your directions what to do with them. I advised that those not fit to kill should be sold, recording the marks, that Whig owners might receive the money for which they sell respectively. It will cost more than the value of them to keep them in a flock. They are driven up the country to be out of the enemy’ s way, and the Colonel will follow your directions as to the disposition of them.

He also explained the plans of the militia officers. “At a council of the Field Officers this morning, a majority of them advised to remove the brigade of Militia back again to Chatham, for which they assigned these reasons: Many of the Militia, rather fond of plunder and adventure, kept a continual scouting, which kept out so many detached parties that the body was weakened; and the enemy being now stronger at Elizabethtown than they are, they thought they would better serve the cause by lying at Chatham till the expected army approaches for their support.

Colonel Ford also desires your directions with respect to the arms, horses, or other property taken with any of the enemy. The parties who take them think themselves entitled to these things.

I enclose you some examinations. Colonel Ford thinks, from the circumstances of the wagons taken up at Brunswick to go empty to Trenton, that the enemy intended to retreat. I hope their retreat will be guarded against. I have very much suspected as soon as our whole Army is over the river they will return to reduce this Province, leaving only part of their Army at the river to prevent ours returning, till they have plundered us at their pleasure.”

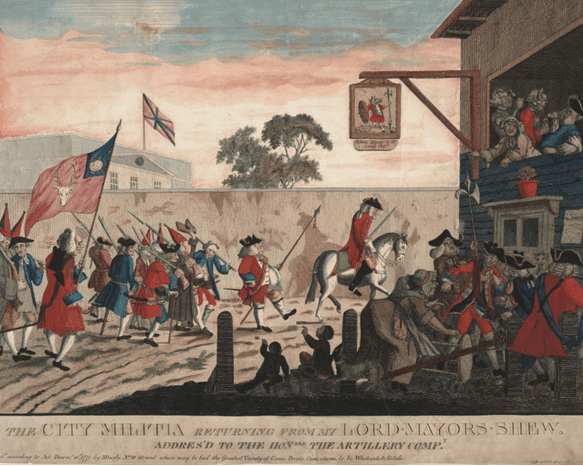

The Battle of Springfield, December 17, 1776

December 1776 was one of the lowest points of the American Revolution for the Patriot forces. General Washington and his small army had been driven out of New Jersey into Pennsylvania. Four days earlier on Friday the 13th, General Charles Lee had been captured by a British cavalry patrol in a tavern in Basking Ridge. Most of the New Jersey militia had disbanded and fled in the face of the British invasion. The only Patriot force of any note left in the state were militia from Morris, Essex and Sussex counties under the command of Colonel Jacob Ford, Jr.

The British army controlled New Jersey’s central core running from Elizabeth and Newark through New Brunswick, Princeton, Trenton, to Burlington. Unaware of what Patriot forces might linger on their flanks, the British sent troops into northern New Jersey to investigate.

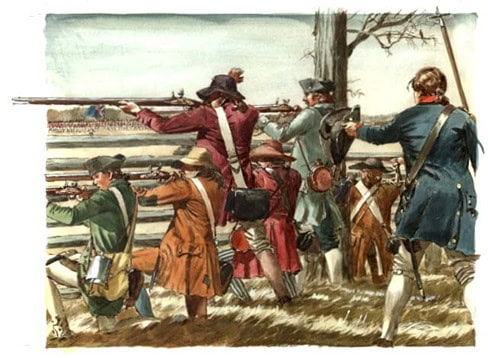

John Cleves Symmes, the colonel of the Sussex County militia recalled that on December 17th, “I,… the having the command of the Militia from the County of Sussex in the State of New Jersey, lay at Chatham, in said State, with other Battalions of Militia forming a Brigade under the command of Colonel Jacob Ford, when Colonel Ford had advice that the British troops to the number of eight hundred men, under the command of General Leslie, had advanced to Springfield within four miles of Chatham. Colonel Ford thereupon ordered me to proceed to Springfield and check the approach of the enemy, if possible. According to orders, I marched to Springfield with a detachment of the Brigade, and attacked the enemy in Springfield that evening.”

Samuel Freeman, of the Morris County Militia recalled the fighting, “Were then ordered to Essex County under Col Jacob Ford, met the enemy at Springfield where we had an engagement with them on this occasion, some militia from Sussex County were present with us. Orders were given for those in the front ranks to fire & then retire to the rear, the rear rank then to advance & fire & retire in their turn. The Deponent was in the front rank & when orders were given to fire, the rear rank fired directly thro’ the front rank. Two fell, by side of this deponent, shot thro’ the legs, the balls passing in at the calf of the leg & out at & thro the shin bone, breaking their legs. Robert Pollard, belonging to the Militia, was shot thro the lungs but was not killed. This Deponent found 3 bullet holes thro his coat after the engagement was over.”

Their method of one rank firing and then falling back behind the rear rank to reload is a different form of drill than what was used later in the war. But early in the war a variety of drill manuals were in use. For relatively inexperienced militia, this drill makes sense. The men probably felt more vulnerable while loading their muskets. By falling behind the firing line while loading they had a feeling of “protection” of a rank of men between them and the enemy. However, in the heat of battle all this extra movement didn’t work well with inexperienced troops. Obviously, Ford’s men were nervous and new to battle causing everyone to fire at the same time, despite the orders.

Samuel quickly saw cost of war, with men around him being shot. Interestingly both men are hit in the lower leg. Many battle accounts mention musket volleys flying too high over the soldiers’ heads, but in this case two shots were very low. My guess is that the British and Americans were firing from a distance and gravity over that long distance was pulling their shots lower and hitting the men’s legs. But during the skirmish other shots went higher hitting one man in the chest and three shots going through Samuel’s coat. Perhaps as the opposing lines got closer to one another, the shots were going higher.

The wounding of Robert Pollard made an impact on the soldiers of the Morris County militia and several men recalled the scene in their pension applications. Job Brookfield stated, “Robert Pollard of the Sand Hill company was shot through the breast, but was not killed, altho’ his breath passed through the wound, bubbling through it with the blood at each breath. He survived & recovered.” Jacob Lacy added, “…We were posted on the farm & not far from the home of Simon Briant on rising ground & Robert Pollard a militia man of Chatham, well known to me, was shot through the lungs & the blood & air of his breath bubbled out at the wound at each breath he gave. He stood but a few rods from me when he fell & yet he recovered from this terrible wound & lived many years after.”

Colonel Symmes commanding the Sussex County mentioned, “In the skirmish Capt. Samuel Kirkendall of the Sussex Militia was wounded in his hand, his was split, by a musket shot, from his middle finger to his wrist, by which wound he has lost the use of his right hand.”

Job Brookfield also noted that, “Col. Spencer of Elizabeth town [commanding Essex County militia] was with us on this occasion & had his horse shot under him. He dismounted & carried off his saddle with him.”

While Abraham Fairchild recalled, “there were several men belonging to the Militia wounded in it & Doctor Johnes & Doctor Budd both were engaged in dressing the wounded. Robert Pollard was one of the wounded being shot through the breast & back & afterward recovered. Some of the wounded were taken to Chatham & placed under Doctor Johnes care.”

On December 18, 1776, General Heath noted, “Intelligence was received, that some of the Jersey militia had had a skirmish with a body of British troops under Gen. Leslie, near Springfield. Both parties retired. Of the militia, several were killed and wounded.”

Colonel Ford commanding a force of militia from Morris, Essex and Sussex counties had run into 800 to 1,000 British soldiers near Springfield, New Jersey. Fighting continued until darkness caused both sides to withdraw. Colonel Ford and his men retreated to Chatham where that night he wrote to Major General William Heath: “We have Since Sun Set had a Brush with the Enemy 4 Miles below this, in which we have Suffered, and our Militia much Disheartened. They are all Retreated to this place and will in all probability be Attacked by Day Break. The Enemy we have Reasons to believe are Double our Numbers… If in your wisdom you can Assist us we may possably Beat them yet, but without your aide we can’t Stand.” Fortunately, for Colonel Ford, the British had no intention to continue the fight and withdrew to Elizabeth.

From Chatham, Colonel Ford updated General Heath at 5 o’clock in the morning on December 18th. “Since writing my last I have certain intelligence that the troops we engaged last night were General Leslie’ s brigade, who marched some few days since from Elizabeth-Town to the southard. They received an order to counter-march to the same place. That brigade is from twelve to thirteen hundred strong, and the Waldeckers upwards of four hundred. At Spank-Town, six miles to the southard of Elizabeth-Town, there is five hundred British troops. This is all the enemy you have to combat in this country at present. We are not certain whether the enemy who attacked us have or have not yet returned to Elizabeth-Town. Lord Stirling is on this side the river Delaware, with a small detachment joined to General Sullivan, with orders not to recross the river, if my intelligence be good, and I believe it is.”

Archibald Robertson, a British officer, explained the British plans in his diary entry for December 17th, “Three Patroles were ordered out by General Howe’s orders. 2 Battalions under General [Alexander] Leslie to Springfield. He had a small Skirmish with about 250 of the Rebels, had 4 men Wounded. 500 Grenadiers under General Matthews [Edward Mathew] went to Pluckemin. Had 3 men taken not being able to march. A Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Mahood [Charles Mawhood] towards Flemmington met with no Rebels”

Colonel Jacob Ford, Jr., in his December 17th letter to General Heath added, “The Enemy we have Reasons to believe are Double our Numbers. Genl. McDugal is with the Northern Battallions that were Comeing on with Coll. Vose and intends Marching Directly to Genl. Washington. He is this Night in Morris Town 8 Miles West of this and we have no Expectations of his assistance. If in your wisdom you can Assist us we may possably Beat them yet, but without your aide we can’t Stand.

They are Encamped (Say 1000 British Troops) at Springfield and will be joined by 450 Waldeckers from Elizth. Town by the Next Mornings Light. I Know Sir it is not for me nor would I presume to direct you, but if you Can consistently [blotch on paper], I beg and pray you’d come to our assistance The Bearer will give you our Scittuation and that of the Enemy and be your Guide, after which you will be a proper judge whether to Beat up their Rear or March in their Front and join us, or Rather Suffer us to join you, and march the Whole Down upon them.”

Brigadier General Alexander McDougall, commanding the Continental Army troops in the area reported to Washington on December 19th, “an express arrived at night with information that Colonel Fords Militia had an Engagement with the Enemy at Springfield, and that he expected it would be renewed the next morning to gain the pass of the mountains. [Hobart Gap in Watchung Mountains on route to Morristown] The Country in General being greatly discouraged, and on the Eve of making a Surrender of this State, I Judged it my Duty to order those Regiments to march at four A.M. to support Colonel Ford. The Enemy early the next morning retired towards Spank Town.” He added in a postscript, “Col. Ford has had, from 800 to 1000 of the Militia Collected. Now about 700.”

McDougal also reported to Washington that the people of Morris County were petitioning for Continental Army troops to be stationed in Morristown for their protection. They wrote,

“The distressed situation of this state & the eminent danger of this County filled at present with most of the persons & property of the well affected people of this part of the Province induces us most earnestly to request you to detain the Troops now in this neighbourhood on their march from Tricondaroga. We had Genl Lees [captured on Dec. 13th after passing through Morristown] express promise that this detatchment should be detained here for the protection of this state. And altho’ his Letter to the Commanding officer does not contain so explicite an order for that purpose as we could wish, Yet there is sufficient evidence that this was his intention from a full view of the necessity & importance of such a measure. You are also sensible that this is the desire of Genl Heath. And from what you, Sir see & hear, we cannot doubt but it appears in the same light to yourself.

We are truely sensible of the necessity of a large Force with Genl Washington. But while the Enemy are so disperced it cannot be expected the whole Body of our Troops can be all at one place. Part of our Militia have been called out of the Province. And if we had the whole what coud they do against the Enemy the main Body of which is in this state. Yet with the support of these Troops we hope to collect a larger Body of the militia than we have at present & by defending important passes secure a great part of this state & it may be in Time regain the whole. But, Sir, we must speak the painful truth, if these Troops are not detained, the militia collected now will grow dispirited, soon dwindle away & this state be lost. We beseech you consider these things & grant us such relief as is in your power. We honestly declare, that so far as we know our hearts we speak not from a partial regard to one part of the Continent but as if the whole was our own.”

The petition was signed by “Jacob Ford [a judge and Col. Ford’s father] Silas Condict [of the Provincial Council, Caleb Camp [of the Provincial Assembly], Alexander Carmichael [Charmain of the Committee of Safety], Timothy. Johnes [Presbyterian Minister and Col. Ford’s father-in-law] Benjamin Hait, A. Mainhorte, Jacob Van Artsdalen, [3 Ministers], Jacob Ford Junr Colo. Commandant of the Militia, and James Caldwell [Presbyterian minister of Elizabethtown].

General Heath tried to reassure Ford and the people of Morris County writing on December 18th, “I have great expectations of Col. Vose’s remaining with you, at least a few days, until he can receive express Orders from Genrl Washington, to whom I have desired him to apply for further directions” General McDougal advised Heath, “I think it most prudent, & woud advise you to detain the Troops under the Command of Colo. Boise [Vose] untill you shall know his Excellency Genl Washington’s Pleasure respecting them after having given him a full Account as well of your Situation & Strenghth as that of the Enemy in your Quarter—At the same Time I woud not be understood as giving any positive Order concerng them as they do not belong to my Divission.”

General McDougal also told Heath, “I coud wish to hear from you & Colo. Ford every Day that I may know the Situation & Strenghth of the Enemy in your Quarter as it may so happen that we may be able to attack them in different Quarters at the same Time to great Advantage without exposing this Part of the Country—I woud only add that my Sentiments respecting the Detaining of Boises [Vose’s] Troops is Strenghthened by that of Genl Parson’s & Clintons Opinion on that Subject.”

New Jersey’s General William Maxwell was sent to Morristown to take over command of the forces in the area and he reported to Washington on December 29th, “I arrived here the 24th past 11, ocloack at night found things not in so good a state as I could wish.” Maxwell also reported on Colonel Ford and his attempts to recruit a regiment of three months levies and his hope to turn them into a fulltime Continental Army regiment. “Before I came here they had begun the Recruiting under Coll Ford to the first of April and seemed to go on rapidly [three months levies]…Coll Ford makes no doubt of making up a full Regiment out of them with a few others for three years or during the War [fulltime Continental regiment] shortly after he has the Regiment formed if your Excellency will give him assurance that he shall Have the Command of them when so engaged. I think it is the most likely place to raise the Regit you spoke of and from the small accquaintance I have had with Coll Ford he appears very zealous for the service and I believe will command them with a good dale of reputation.”

Ford’s Collapse – January 3–4, 1777

Colonel Jacob Ford, Jr. returned to Morristown to reorganize and resupply his militia. It was also a fork in the road of Jacob Ford’s military career. While serving as a colonel of the Eastern Battalion of the Morris County Militia Ford was also serving as a temporary Brigadier General of the New Jersey Militia and was a potential candidate for the position permanently.

At the same time, Jacob Ford also was appointed a colonel of three-month levies. These were short-term troops who would serve in the Continental Army, while Washington and Congress recruited a new army that would serve for at least three years.

Ford hoped that if he recruited well his short-term levies could be convinced to serve for three years and the regiment would be made into one of the new additional Continental Army regiments with him in command.

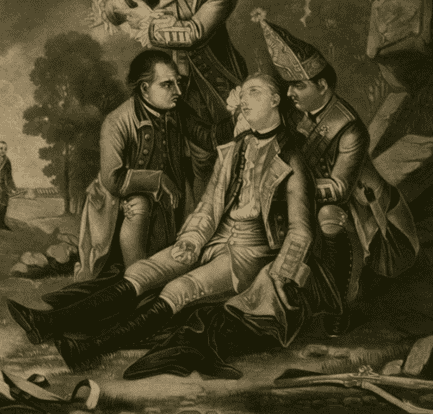

But things changed dramatically for Ford on January 4, 1777. His son Timothy described the day in a 1793 petition to get his mother a widow’s pension, “considerable part of his Regiment being recruited, [Jacob Ford, Jr.] lay in quarters along with the militia at Morristown, on the 3rd day of January, 1777. The next day being the 4th, you [General William Maxwell] gave orders for those troops to march to Chatham; and that same day, while my father was in arms at the head of the Regiment in execution of those orders, he was seized with a sudden illness, lifted from his horse and brought home;… the Regiment marched to Chatham the day he was taken ill, and continued out … forming a part of your general command on the lines. Dr. Campfield, who regularly ought to have attended him, marched with the Regiment to Chatham, leaving him to Dr. Johnes (who was Surgeon of my father’s Regiment of Militia), and Dr. Johnes attended…”

His doctor, Timothy Johnes, Jr. added, “The Army was ordered to march, “and the Colonel not-withstanding a mortal cold he got on the retreat still attended under Arms in front of the Regiments, when he was struck all at once with a Pleurisy and delirium, he was lifted from his horse and borne off the field as the March began. A small Militia Guard and myself as Surgeon stayed behind to attend him.”

Soldiers in the House – January 6–18, 1777

Colonel Ford collapsed on Morristown Green the day after the battle of Princeton. Following the battle Washington army marched north and arrived at Morristown on January 6, 1777.

With smallpox spreading through the army and the civilian population, Washington wrote to Dr. Shippen on the 6th, “Finding the small pox to be spreading much and fearing that no precaution can prevent it from running thro’ the whole of our Army, I have determined that the Troops shall be inoculated. This Expedient may be attended with some inconveniences and some disadvantages, but yet I trust, in its consequences will have the most happy effects. Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army, in the natural way, and rage with its usual Virulence, we should have more to dread from it, than from the Sword of the Enemy…If the business is immediately begun and favoured with the common success, I would fain hope they will be soon fit for duty, and that in a short space of time we shall have an Army, not subject to this, the greatest of all calamities that can befall it, when taken in the natural way.”

That same day Captain Thomas Rodney wrote in his diary, “We left Pluckemin this morning and arrived at Morristown just before sunset. The order of march, was first a small advance guard, next the officers who were prisoners [captured at Battle of Princeton], next my Light Infantry Regiment in column of four deep; next the prisoners [captured at Battle of Princeton] flanked by the riflemen, next the head of the main column, with the artillery in the front.

Our whole Light Infantry are quartered in a very large house belonging to Col. Ford having 4 rooms on a floor and two stories high.”

On January 7, 1777, Rodney noted in his diary, “This morning General Washington appointed my Infantry Regiment to be his own guard…This day I was myself officer of the Guard whose duties consist in mounting 26 of the infantry every day…When I waited on the General to fix his guards, there was no guard house prepared…now there was none to be had, excepting one that had been used as a hospital; I told the aide that all the volunteers under my command were gentlemen and should not lodge in such a house…the General…requested that I would let our own quarters be the guard house, which was about a mile from him; so the guards were relieved at that distance.”

At this point Jacob Ford is in sick in his bedroom upstairs in the Ford Mansion while Thomas Rodney and the men of his light infantry troop were using the house both as their quarters and as a guard house. This meant soldiers would have been awake in the house 24 hours a day, ready to respond to any emergency.

This begs the question, how many soldiers were there in the Ford Mansion? Rodney mentioned “mounting [guards] 26 of the infantry every day.” Guard duty was normally rotated. While some men were on guard duty others were off. This could mean that two or three times the “26 of the infantry” were living in the Ford Mansion. Rodney had also noted that “Our whole Light Infantry are quartered in a very large house belonging to Col. Ford.” Later, on January 14th Rodney commanded 40 men at a funeral. He mentioned that they were all part of his command. This could mean that at least 40 soldiers were living in the Ford Mansion with the family.

My guess is that the Light Infantry would have used two or four of the rooms on the first floor as quarters and guard rooms while the bulk of the men may have slept in the attic. I assume the Fords would retain their bedrooms on the second floor as well as their kitchen and pantry. Outbuildings such as a barn could potentially have been used to quarter soldiers as well.

The only account we have of the home’s occupation from the Ford’s perspective comes from Gabriel Ford’s interview with Benson Lossing in 1848. Gabriel Ford recalled that some of the officers: “were sons of some of the leading men of that state [Pennsylvanis] – gentlemen by birth, but rowdies in practice. They injured the room very much by their nightly carousals.”

News of Colonel Fords efforts with the militia had reached the halls of the Continental Congress, who had fled to Baltimore. Samuel Adams wrote to his cousin John Adams on January 9th, “The Progress of the Enemy thro’ the Jerseys has chagrind me beyond Measure, but I think we shall reap the Advantage in the End. We have already beat a Part of their Army at Trenton,… The late Behavior of the People of Jersey, was owing to some of their leading Men, who instead of directing and animating most shamefully deserted them. When they found a Leader in the brave Coll. Ford they followd him with Alacrity.”

By January 10, 1777, the enlistments of Rodney’s men had expired. He reported that “most of them seemed determined to go home…but none of them went but Mills.”

Ford’s Death and Funeral – January 11–13, 1777

On January 11, 1777, Jacob Ford, Jr. succumbed to his illness and died of pneumonia. In a gesture to Ford and the New Jersey militia, General Washington ordered the Light Infantry troops, who occupied the Ford Mansion, to bury Colonel Ford with “the honors of war.” Captain Rodney noted in his diary, “The Infantry were called on to-day to bury Col. Ford with the honors of war and I appointed Capt. Nezbitt to command.”

The burial took place two days later on January 13, 1777. Ford was interred a mile away at the Presbyterian Church in Morristown. The church’s minister, Reverend Timothy Johnes was Ford’s father-in-law and I presume must have officiated at the funeral. The artist Charles Willson Peale, who was an officer in the militia from Philadelphia, attended Ford’s funeral. Captain Rodney did not attend, instead sending a Captain Nezbitt to command the military detail.

Unfortunately, we have no description of Colonel Ford’s military funeral. However, the following day, Captain Rodney presided over another military funeral for Colonel Hitchcock, a Continental Army officer from Rhode Island. Rodney did provide a description of this funeral at Morristown’s Presbyterian Church, and I assume it would have been similar to Ford’s military funeral.

Despite the fact that Rodney and his men were quartered in Ford’s house, Rodney decided not to command the troops at his funeral, instead sending a lower ranking officer. But Rodney did command the soldiers at Hitchcock’s funeral because Hitchcock was a Continental officer rather than a militia officer like Ford. He mentioned his decision in a January 14, 1777, letter to Caesar Rodney, “Yesterday we Buried Col: Ford of the Jersy Malitiar (and owner of the House where we are & an Elegant one it is) with the Honours of War – and To day we Buried Col: Hitchcocks who Commanded a New England Brigade Raised immediately after the Battel of Lexington – The Infantry performed the firings at both – and I Command at the last, he being a Continental officer – yesterday I put the younger officers to do the Service [for Ford], as I have had the Command of the Light Infantry Battalion since the Battle of Prince Town being the Eldest Captn.”

This is Rodney’s description of the funeral for Hitchcock on January 14, 1777, “This day the Infantry were ordered to bury General Hitchcock with the honors of war and as he was a continental officer I took the command myself. Order of the funeral. 40 of the Infantry in 4 lines, 10 in arms reversed in each line, youngest Lieut. In front, Eldest in Center, Capt. In the Rear – followed by the fifes and Drums – [next?] the Bier followed by the mourners – then the officers and the Battalion in lines of Ten as patoons [platoons] in open order as the infantry. This was the order of march, but the Battalion first stood in the order described and wheeled to the wright and left backwards and formed a line for the Infantry Bier, mourners, officers and etc. to pass through then closed up and followed as described. When we got near the grave the youngest Lieut. Gave the word for the Infantry to wheel to the Right and Left backwards to form a lane the corpse and mourners to pass through and to rest on their arms – buried his corpse, mourners and officers past through and I followed them and took post then in the front and as I got there ordered the Infantry to shoulder and wheel to the Right and left inwards and march up in Quick Time and close order to the grave – then gave the word to wheel to the left and form Battalion, then make ready and fire repeated three Vollies – when the Infantry formed a lane the Battalion did the same and rested on their arms reversed and shouldered and closed up at the same time also and followed to the grave but did not fire -This day most all of my company set off home though I tried all in my power to prevail on them to stay until the brigade went.”

By January 18, 1777, Captain Thomas Rodney and the last of his men left the Ford Mansion to return home.

After Ford’s Death

After the death of Jacob Ford Jr., Oliver Spencer, who had commanded the Essex County Militia at the Battle of Springfield, took over command of Colonel Ford’s new state regiment of three month’s levies on February 3, 1777. These short-term troops were meant to help hold the army together until long term troops could be recruited. Meanwhile, Spencer had been commissioned colonel of one of the new Sixteen Additional Continental Regiments on January 15, 1777. Later this unit was commonly known as “Spencer’s Regiment.” If Jacob Ford had lived, this could have been his career path.

But with the army in transition, Washington still needed the help of the Morris County militia. He wrote to General Maxwell on February 18, 1777. “I wish the Morris County Militia could be prevailed on to stay some time longer—The Enemy are certainly reinforced & will no doubt attempt in a few days to make their situation more comfortable—should they do so, We shall not be able to make an effectual Opposition, if the Troops now in service retire to their Homes, & they will again be reduced to that Misery from which they were but just now releived merely by their exerting themselves manfully—Make them acquainted with this, & let them also know that their Families will be under not the smallest danger of catching the Small pox—I have taken every Possible Care of them & have Guards placed over every house of Innoculation to prevent the Infection’s spreading—At any rate they must remain ’till the Essex Militia releive them, who are ordered out every Man immediately.”

The Morris County militia and other Jersey militias continued to serve throughout the war. John Adams praised them in a letter writing, “One Thing is certain, that in the Jersies his whole Army was seized with Terror and Amazement. The Jersey Militia, have done themselves, the highest Honour, by turning out in such great Numbers, and with such Determined Resolution.”

Sources

Introduction Sources

Early 1776 Sources

- Statement of Job Loree for Israel Aber Pension Application W.16,800, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Samuel Freeman Pension Application S 4,290, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Statement of Isaac Bedell for widow of Timothy Johnes, W 468, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Statement of Job Low for widow of Timothy Johnes, W 468, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Statement of Luke Miller for widow of Timothy Johnes, W 468, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Israel Lee Pension Application S. 23767, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Abraham Fairchild, Pension Number W787, Statement for Widow of Timothy Johnes, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- To George Washington from Jacob Ford, Jr., 19 April 1776

- From George Washington to Brigadier General Hugh Mercer, 4 July 1776

- To George Washington from Brigadier General Hugh Mercer, 8 July 1776

- Orders of General Williamson to Colonel Ford, American Archives, Peter Force

- To George Washington from William Livingston, 27 November 1776

Mud Rounds Retreat Sources

- Samuel Freeman Pension Application S 4,290, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Statement of Isaac Bedell for widow of Timothy Johnes, W 468, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Statement of Job Loree for Israel Aber Pension Application W.16,800, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- To George Washington from General Matthias Williamson, 8 December 1776

- Israel Lee Pension Application S. 23767, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Benoni Hathaway Pension Application S.538, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Letter from Rev. James Caldwell to General Lee, 12 December 1776, American Archives, Peter Force

Battle of Springfield Sources

- Charles H. Winfield, “Life and Public Services of John Cleves Symmes,” New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings, 2nd series, V (May 1877)

- Samuel Freeman Pension Number S 4290, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Job Brookfield Pension Number S 3080, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Jacob Lacy Pension Number S 4498, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Abraham Fairchild Pension Number W787, National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry.com

- Major General William Heath, Memoirs of Major-General Heath

- Colonel Ford to General Heath, December 17 and 18, 1776, American Archives, Peter Force

- To George Washington from Brigadier General Alexander McDougall, 19 December 1776

- To George Washington from Brigadier General William Maxwell, 29 December 1776

Ford’s Collapse Sources

- September 21, 1793 – Timothy Ford at Morristown to General William Maxwell, Proceedings of the NJ Historical Society, New Series, Vol. 2 (April, 1925)

- Morris County Court of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace Record Book 1779-1795, Certificates concerning Revolutionary War Pensions, NJ Historical Society Manuscript Collection No. 529

Soldiers in the House Sources

- Washington to Doctor William Shippen Jr., 6 January 1777, Writings of Washington, Vol. 6

- Diary of Captain Thomas Rodney, 1776–1777, Historical Society of Delaware

- Benson J. Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution

- To John Adams from Samuel Adams, 9 January 1777

Funeral Sources

- Diary of Captain Thomas Rodney, 1776–1777, Historical Society of Delaware

- “Charles Willson Peale, Artist – Soldier,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 38 (1914)

- Peale, Charles Willson diary, 1765–1826

- January 14, 1777 Letter to Caesar Rodney, from Letters to and from Caesar Rodney 1756–1784

After Ford’s Death Sources

- To George Washington from Brigadier General William Maxwell, 9 February 1777

- From George Washington to Brigadier General William Maxwell, 18 February 1777

- From John Adams to James Warren, 11 June 1777

Illustration Sources

- Silhouette – Brown Digital Repository

- Maps – Library of Congress

- Valley Forge defenses illustration

- Portrait of Rev. James Caldwell – Find a Grave

- View of the Narrows and fleet – NYPL Digital Collections

- Climbing Palisades – American Battlefield Trust

- Washington’s Crossing image – George Washington’s Mount Vernon

- Battle and militia illustrations – Brown Digital Repository

- Ford Mansion – Morristown National Historical Park Collection

- Funeral and marching scenes – various historical illustration sources