Soldiers’ Story: The Musicians of War

Today we enjoy fife and drum performances at parades and celebrations. During the Revolution, military field music had little to do with entertainment, but instead was a vital communications system. The deep boom and steady cadence of the drum and the piercing shrill whistle of the fife could be heard up to a mile away, even cutting through the noise of combat. Chief among the duties of the field musicians was the playing of “calls” or “duties,” which are distinctive beatings accompanied by short tunes.

Many of the Continental Army’s early failures can be attributed to the lack of standardized music which caused confusion among the troops. Baron von Steuben recognized this and revamped all the music into standard rudiments documented in his training manual, and heavily drilled the troops to understand and follow these standardized musical instructions.

In Camp

When in camp, a soldier’s entire day was dictated by calls by the musicians, including those of reveille, meal time, assembly, performing fatigue details, and retreat at sunset. The last song at night was called a “tattoo,” named for the act of “turning the taps to,” meaning that tavern keepers would tighten the taps on their barrels of ale and close for the night. Today, this ceremony is known as “Taps.”

You can hear some of these camp calls at the following link:

http://www.warnersregiment.org/Camp%20Duties2.html

In Battle

Turn Left

Turn Right

Turn About

On the battlefield, the fifes and drums directed the loading of weapons, firing, marching, and retreat. Here are some of the signals:

You can hear some of the battlefield calls at:

https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/music/

Additional battlefield musical signals included:

- “To Arms”: a general alarm, used when the army was surprised.

- “Cease Fire”: a well-understood tune on both sides.

- “Parley”: a request to pause the action to allow negotiation or to remove wounded from the battlefield.

Morale Boost

The music also helped boost morale and maintain esprit de corps, and proved vital in the wake of severe battlefield defeats or during severe hardships such as long, hot marches or cold winters of suffering.

In addition to their signaling duties, many musicians adapted contemporary dance songs to entertain soldiers, officers, and visiting dignitaries. Dances, balls, time in a hut or around a campfire, were all ways that music was used to build morale and let men blow off steam or grieve the losses of friends and family.

Both the British and American armies used the widely known martial melody “Yankee Doodle” to make a musical statement. The British used it to express contempt for the provincial rusticness of the Americans. Meanwhile it became “The Lexington March” for the Americans, a symbol of their courage and newly found confidence.

The Instruments

The fife is a cylindrical, wooden, side-blown instrument with six finger holes and no keys. Most fife music is limited to the keys of D, G, and A.

The snare drums were made of wooden shells and hoops, calfskin heads and gut snares, ropes laced through and around to create tension, and wooden mallets or sticks to beat them. A bass drum was sometimes used — a large barrel drum strapped around the shoulders and beaten vertically.

The Musicians

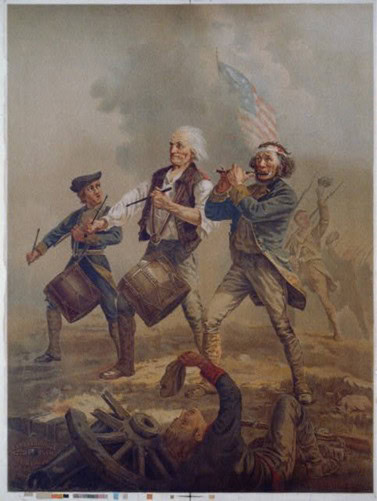

Yankee Doodle 1776 by A. M. Willard

During the war, each company provided a fifer and drummer to the regiment. Sometimes (but not always) the musicians were young boys who were orphans or followed their officer fathers into the army. Bennett Cuthbertson, a military theorist, recommended enlisting boys as musicians, saying “…their duty is not very laborious, it matters not how young they are taken…” But not all agreed: Morris County fifer Swain Parsel said fifing injured his health and switched to infantry service.

Often African American soldiers were chosen as drummers because this prevented them from carrying a weapon. In the South, there was fear that arming Black soldiers might encourage them to fight for their freedom.

Their uniforms were inverted colors of their regimental uniforms, marking them as non-combatants and allowing their captains to find them quickly in battle.

Their visibility and lack of weapons also put them at great risk. Morris County musicians wounded or killed include: Isaac Bedell (twice wounded), John Billings (shot in the leg), John Lavender (died 1780), Swain Parsel (twice wounded), and John D. Piatt (wounded, captured, and later injured by a horse).

We honor all the Morris County Revolutionary War musicians:

- Drummers: Jabez Bigelow, John Clearman, William Conkling, Ephraim Hayward/Howard, Daniel Jones, Simon/Simeon Van Winkle, Henry Welter/Walters, Joseph Williams

- Fifers: Daniel Applegate, Benjamin Baldwin, Isaac Bedell, John Billings, Peter Dorland, John Lavender, Caleb Meeker, Swain Parsell, John D. Piatt, James Rogers, Elisha P. Skellenger

- Master of music at camp: William Shippen

- Musician (unspecified): Samuel Brown

The following link is a 13-minute performance by the Army’s modern-day Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps:

https://www.loc.gov/item/webcast-9129/

Sources

- Camus, Raoul F., Military Music of the American Revolution, 1976

- DAR Genealogical Records System, Ancestor files, https://dar.org

- Hoskins, Barbara, Men from Morris County New Jersey Who Served in the American Revolution, 1979

- Midgeley, Anne, Call to Arms, 2015

- Various Revolutionary War pension files, NARA RG15

- Stryker, William S., Official Register of Officers and Men of New Jersey, 1872

- Multiple online resources including Mount Vernon, Colonial Williamsburg, NJ Fifes & Drums, and others.